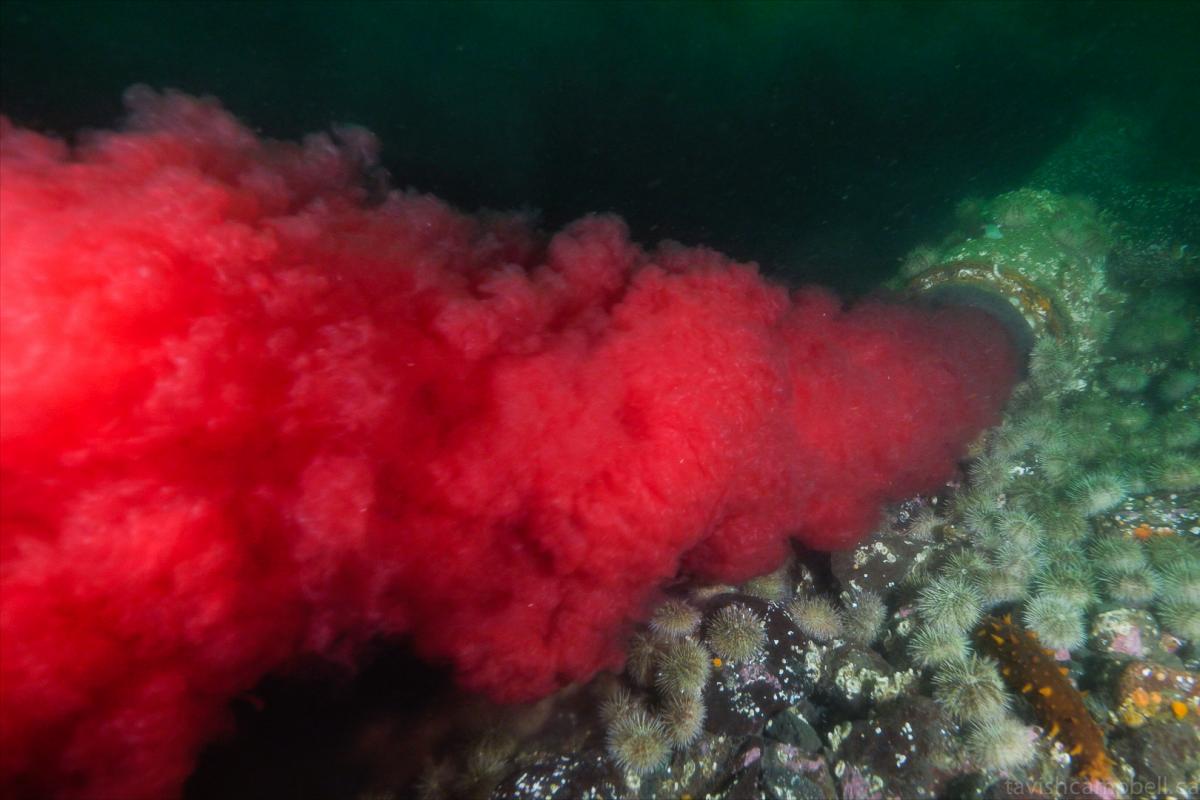

Shocking video footage released this week by BC photographer Tavish Campbell and replayed by media across the country shows a disturbing torrent of bloody wastewater from fish farm processing plants pumping directly into the ocean. The video captures the bloodwater streaming into the sea from two sites: the first near Brown’s Bay on Vancouver Island, next to a wild salmon migration route in Discovery Passage, and the second, into fish habitat in the Tofino harbour.

Blood Water: B.C.’s Dirty Salmon Farming Secret from Tavish Campbell on Vimeo.

Fish processing facilities produce this wastewater, which contains the blood and entrails of farmed Atlantic salmon. Tavish told us how he collected samples at the Brown’s Bay site, where he captured his footage: “I swam up to the discharge pipe and held a plankton net over the end of it, which filled with chunks of blood and fish scales.”

These samples tested positive in a laboratory analysis for intestinal worms and piscine reovirus (PRV), a highly contagious virus that most farmed salmon carry, which has been linked to a threatening disease in salmon known as heart and skeletal muscle inflammation (HSMI). HSMI causes muscle degradation and is frequently fatal to farmed Atlantic salmon. It is considered to be the third most important salmon disease in Norway.

Wild salmon are key species in the coastal Pacific ecosystem. They are food for people and marine mammals, including the highly endangered southern resident killer whales; provide commercial and recreational fisheries jobs; and are central to the culture and ceremonial practices of Indigenous peoples, and indeed all people on the coast of BC. Potentially exposing wild Pacific salmon to disease through this discharge of waste is deeply troubling, and points to a gap in our regulatory safety net.

Photographer Tavish Campbell captured images and footage of the bloodwater discharge. (Photo: Tavish Campbell)

So, is it legal?

People from all over the province have asked us about the legality of the bloodwater discharge. The short answer is that the practice of discharging bloodwater from fish plants is legal for now, even if the blood contains instances of PRV. Currently, the federal government regulates fish farms and animal health, while the province regulates fish processing facilities. This has created two separate systems that are not clearly linked, leaving regulatory gaps that threaten the health and habitat of wild salmon and other marine organisms.

Fish blood from fish farms

It appears that under the current regulations, fish blood can legally enter the ocean from open-net pen fish farms. The federal Fisheries Act prohibits unauthorized deposits of blood and other biological substances into the water (which likely qualify as "deleterious substances" under the Act), except when they come from fish farms directly. Under the Aquaculture Activities Regulation, fish farms can deposit fish blood and other matter (such as fish feed and feces) directly into the sea, though they must monitor for disease and other parameters, and to minimize the impact of the discharge.

Fish blood from fish processing facilities

It appears that fish blood can also legally enter the ocean from fish processing plants. Though the Fisheries Act prohibits the deposit of "deleterious substances," there's an exception when the release is authorized. It is not clear whether this exception includes provincial authorizations. The provincial Ministry of Environment regulates wastewater discharge from these plants through permits under the Environmental Management Act. We looked at the permit held by the Brown’s Bay fish processing facility, which requires the company to follow provincial and federal procedures when dealing with diseased fish, bloodwater treatment and disease monitoring.

Though the permit does not name the procedures that the company should follow, the practice captured in Tavish’s footage may violate the 1975 non-legally binding Fish Processing Operations Liquid Effluent Guidelines, which restrict the discharge of bloodwater and require treatment of contaminated process water.

What about PRV?

Both fish farms and fish processing facilities must monitor fish and fish blood for disease. So why is it legal to discharge bloodwater that contains PRV, despite the fact that it has been linked to HSMI?

Although discarding diseased fish parts into the water is prohibited under the federal Health of Animals Act and its regulations, PRV and HSMI are not listed as reportable diseases under the Act. So it appears that under the current regulations, it is legal to discharge fish processing water that contains instances of this virus.

This is a bigger issue than just one processing plant: over 80% of farmed salmon in BC carry PRV. However, under current regulations, farmed fish are not tested for the virus. Scientist Alexandra Morton and Ecojustice are in court with the federal government arguing that the government has been acting illegally by issuing licences allowing the transfer of farmed salmon without testing for the virus. Transferring fish into fish habitat or fish farms that carry disease or disease agents is prohibited in the Fishery (General) Regulations under the Fisheries Act.

Bloodwater discharge from the fish processing plant. (Photo: Tavish Campbell)

What can be done?

Wild salmon are under assault from a slew of forces: pollution, changing ocean conditions, warmer waters, and possibly open-net pen aquaculture itself, as the 3-year judicial inquiry led by Mr. Justice Cohen found back in 2012. Protecting wild salmon appears to have been lost in the complex division of responsibilities between the provincial and federal governments for oversight of fish farming operations.

Though this fish processing plant may have been treating the bloodwater to the standard of the current regulations, it is apparent that these laws are not strong enough to protect wild salmon from disease.

Members of the Musgamagw Dzawada'enuxw and ‘Namgis nations have been occupying fish farm sites in the Broughton Archipelago off northern Vancouver Island since August, and want the fish farms removed from their territory. Tavish’s video and First Nations’ occupation of fish farms highlight the environmental and public health risks associated with aquaculture on the Pacific coast, from both cultivation of fish and fish processing. We, like many others, are concerned about the lack of adequate regulation, oversight and enforcement at all stages of fish farming and processing.

Though the Province is responsible for inspecting some of these facilities, ultimately the protection of fish and fish habitat in marine environments falls to Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO). As a DFO workshop noted back in 2003, we need to address public concern about fish plant effluents, “perhaps the least examined source of marine environmental effects,” and find solutions that include changing the law.

Thankfully, following the release of this footage, the provincial and federal governments both announced investigations into the regulatory requirements for fish processing plants. A month ago the BC government launched a review of the Province’s animal testing laboratory which conducts diagnostic testing on farmed salmon. While the reviews from both governments are a welcome step, there is a larger problem of under-enforcement and regulatory omission, and a need for a hard look at the industry.

There are many plants and fish farms that require action from both levels of government, including clearer regulations and regular inspections and enforcement. The development of a federal Aquaculture Act is an opportunity to introduce stronger standards for this industry and better protections for wild and farmed fish.

We’ll be examining solutions to the issue of bloodwater discharges that may affect not only wild salmon health, but the health of other marine organisms. West Coast is willing to assist with the government-led review processes, and encourages both governments to look at the entire aquaculture industry closely, with the goal of ensuring our laws are up to the task of not only protecting but restoring our wild salmon.

-----

NOTE: This blog post focuses on legal options enforceable through legislation. Theoretically, there may be the possibility of a public nuisance claim if the blood can be shown to be causing harm. However, such a lawsuit would be expensive, and would require plaintiffs to demonstrate that they have a right to bring the case (standing), that the PRV is actually harming fish, that the defendant has no statutory defences, and various other complicated legal issues. Due to the cost and complexity of such a case, we chose to focus on whether or not the more straightforward regulatory tools were sufficient to deal with the discharge of the blood and waste.

Top photo: Fish swim past the bloodwater discharge pipe. (Tavish Campbell)