The federal cabinet’s re-approval of the Trans Mountain Pipeline and Tanker Expansion Project (“TMX” or “the Project”) on June 18, 2019 was hardly shocking news. After all, federal cabinet ministers have been saying for years that ‘the pipeline will be built.’ They even spent $4.5 billion of public money to bail out the project when pipeline company Kinder Morgan decided to abandon it.

The only surprises – sad ironies really – were the fact that the approval came just hours after the federal government declared a climate emergency, and the Prime Minister’s paradoxical definition of free, prior and informed consent as described in the press conference following the approval.

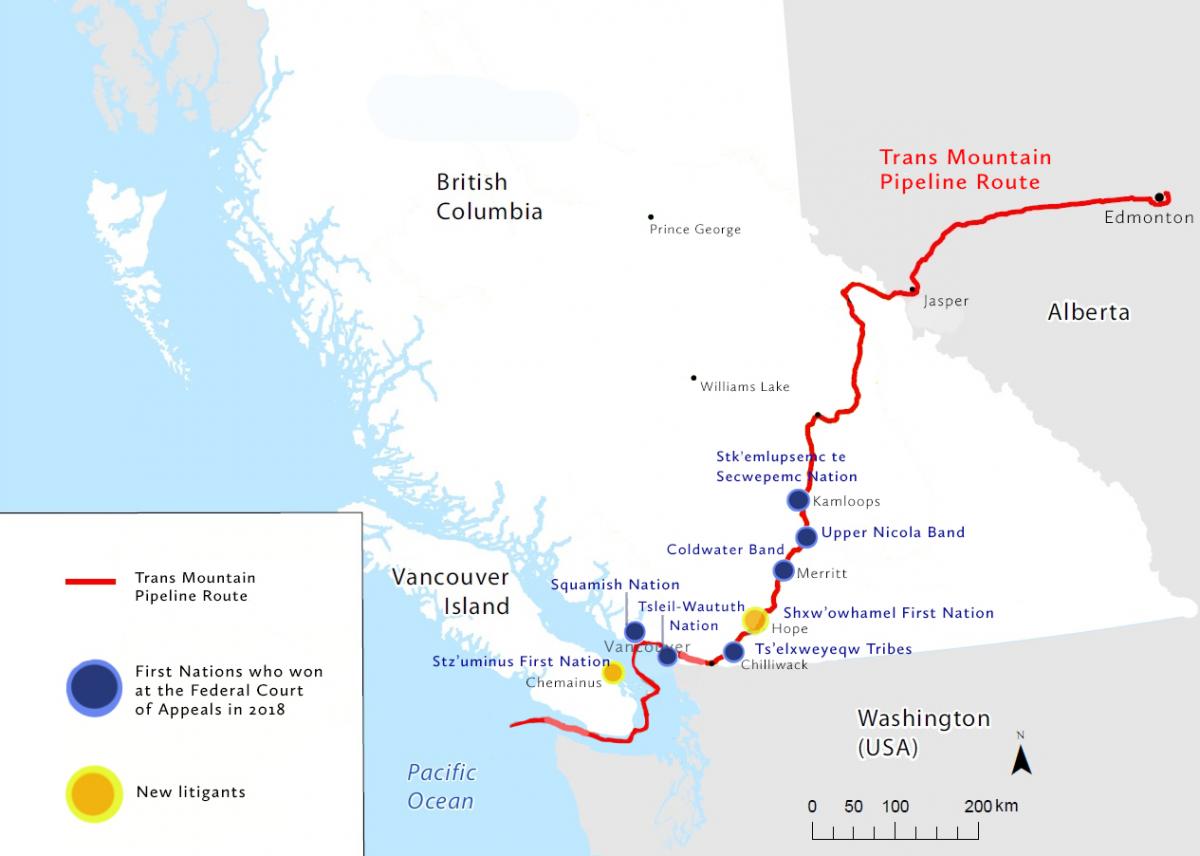

Predictably, the second round of approval faces a second round of legal challenges. According to the Federal Court of Appeal Registry, twelve parties have applied for leave to judicially review the cabinet approval, including eight First Nations, two environmental groups, the City of Vancouver, and a collective of youth climate strikers.

In the first round of lawsuits, six First Nations, environmental groups and municipal governments challenged the original 2016 approval at the Federal Court of Appeal (FCA), and won a decisive victory in August 2018 (the Tsleil-Waututh case). That decision quashed the approvals, and sent the Project back for a redo of the National Energy Board review and constitutionally-required consultation with impacted Indigenous peoples.

We have reviewed thousands of pages of legal documents to provide the following highlights from the applications to the court. In this post, we’ll start by reviewing the timeline of events since the Tsleil-Waututh decision and provide an overview of the law on consultation. Next, we highlight some of the overlapping key arguments from the eight First Nations Applicants, followed by a few specific examples from each Nations’ pleadings, starting from the west and heading east.

Timeline

- August 30, 2018: The FCA releases its decision in the Tsleil-Waututh case, quashing the November 2016 approval of Trans Mountain. The court concluded that the first round of consultation “fell well short of the mark set by the Supreme Court of Canada” (para 6).

- September 20, 2018: The federal government directs the NEB to reconsider aspects of its 2016 recommendation.

- October 3, 2018: The government announces that it will not appeal the Tsleil-Waututh decision to the Supreme Court of Canada, and appoints former Supreme Court justice Frank Iacobucci to oversee a new round of consultation.

- October 12, 2018: The NEB starts a reconsideration process on marine shipping.

- November-December 2018: Justice Iacobucci chairs four roundtables with First Nations in BC and Alberta.

- January-May 2019: Phase III consultations with 129 Indigenous communities

- According to the Federal government, nine teams were deployed – which means an average of 14 communities per team, and three meetings per month for the consultation teams.

- Note: most consultations did not span the entire five-month period.

- June 6, 2019: Deadline for comments on the draft Crown Consultation and Accommodation Report (CCAR).

- June 14, 2019: The final CCAR is provided to cabinet and First Nations.

- June 18, 2019: The federal government announces the re-approval of Trans Mountain.

A brief snapshot of the law of consultation

While the outcome of Tsleil-Waututh was historic, the case did not actually create new law. Rather, the Federal Court of Appeal applied law previously set out by the Supreme Court of Canada on the adequacy of meaningful consultation.

In a series of previous cases, the Supreme Court of Canada has held that the Crown (Government of Canada) has a duty to consult and, where appropriate, accommodate when the Crown contemplates activities that might adversely impact potential or established Aboriginal or treaty rights. This duty is embedded in section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982 as well as in treaties.

Several of these cases were quoted by the FCA in the Tsleil-Waututh decision, and they help to clarify what is required by the Crown in consultation:

- The controlling question in all situations is: What is required to maintain the honour of the Crown and to effect reconciliation between the Crown and the Aboriginal peoples with respect to the interests at stake? (Haida Nation, para 45).

- The depth of the required consultation increases with the strength of the Indigenous claim and the seriousness of the potentially adverse effect upon the claimed right or title (Haida Nation, para 39; Carrier Sekani Tribal Council, para 36).

- As a result, part of the consultation process requires assessing the strength of a nation’s claim and the impact of the proposal on their rights.

- Meaningful consultation is not intended simply to allow Indigenous peoples “to blow off steam” before the Crown proceeds to do what it always intended to do (Mikisew Cree, para 54). The duty is not fulfilled by simply providing a process for exchanging and discussing information. There must be a substantive dimension to the duty (Clyde River, para 49).

- Canadian courts have rejected a generic one-size-fits-all approach to consultation. Rather, each First Nation is entitled to consultation based upon the unique facts and circumstances pertinent to it (Gitxaala, para 236), grounded in their specific historical context and taking into account cumulative effects. (Chippewas of the Thames, para 42)

- Because it is a constitutional requirement, the duty to consult supersedes other concerns commonly considered by tribunals tasked with assessing the public interest. A project authorization that breaches the constitutionally protected rights of Indigenous peoples cannot serve the public interest. (Clyde River, para 40)

- Finally, only after that consultation is completed and any accommodation made can the Project be put before the Governor in Council for approval. (Tsleil-Waututh, para 771)

Fiduciary duty

In addition to the duty to consult and accommodate, the Crown also has a legally enforceable fiduciary duty toward Indigenous peoples. This means that the government (the “fiduciary”) has to act in the best interest of First Nations (the “beneficiary”) when it comes to decisions about reserve lands or established Aboriginal interests such as rights. (Haida Nation, para 18)

A fiduciary must act in the interest of the beneficiary, as an ordinary person would manage their own affairs. A fiduciary cannot benefit personally from their actions, and where there is a conflict between the rights of the fiduciary and beneficiary, the Crown will bear the onus of showing that it did not derive any personal benefit from the situation. (Blueberry River Indian Band)

Aboriginal title and confirmed rights

When rights are confirmed by Canadian courts (or if there is enough information to establish Aboriginal title, whether or not it has been confirmed by a court), infringing those rights must be justified through a three-part test. First, the Crown must discharge the procedural duty to consult and accommodate. Second, the action must be backed by a compelling and substantial objective. And third, the decision must be consistent with the Crown’s fiduciary obligation. (Sparrow)

Summary of First Nations Applicants’ legal arguments

A review of the eight First Nations Applications for Leave reveals a number of patterns. As noted in their arguments, the NEB process was so flawed it could not be relied on by cabinet. The outcome of Phase III consultation was predetermined, the consultation process was rushed, and started with generic accommodation measures rather than trying to understand, and then respond to specific and focused concerns unique to each First Nation.

Consultation teams denied the existence of documents, withheld documents, and in some cases provided altered versions during consultation. Other documents were not disclosed until after the unilaterally imposed close of consultation. The Draft and Final Crown Consultation and Accommodation Reports (CCARs) were flawed and did not allow for meaningful review. Finally, Canada entered into consultation with a closed mind and biased perspective, and was in a conflict of interest as the proponent and fiduciary.

The NEB reconsideration

The NEB reconsideration process was criticized on a number of grounds, including:

- The timeline was too short.

- The scope was too narrow – as it only considered impacts out to 12 nautical miles from shore rather than the 200-nautical mile Exclusive Economic Zone (meaning that it ignored half of the critical habitat for endangered southern resident killer whales), and excluded non-marine impacts.

- The NEB failed to conduct a de novo (new) hearing and adopted older evidence not heard by the new panel.

- The NEB failed to reconsider the need for the project despite updated economic evidence.

- The NEB failed to conduct species-specific assessments for those listed under the Species at Risk Act.

- The assessment of Aboriginal rights was generic, rather than specifically tailored to each First Nation’s rights and title.

- The NEB failed to assess alternatives, including alternative route options.

- The NEB incorrectly applied legal tests under the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act (CEAA) and the National Energy Board Act (NEBA).

- There were new panel members who relied on, but did not hear the evidence from the first NEB hearing, meaning that the NEB reconsideration violates the fundamental principle of natural justice that “he [sic] who hears must decide.”

Any of these errors could result in the Court deciding that the NEB report was inadequate and could not be considered a report that cabinet could rely on in making their decision.

Phase III consultation

Phase III consultation was similarly critiqued on a number of grounds by many of the First Nations Applicants:

- The timeline was too short, in spite of a very short extension.

- There was no meaningful two-way dialogue.

- The outcome was predetermined.

- Canada did not seek to fully understand Aboriginal rights, or the project’s impact on rights before trying to accommodate them.

- “If impacts are not understood, they cannot be accommodated.” (Stz’uminus Memo of Fact and Law, para 105)

- The proposed accommodation measures were generic and introduced prematurely.

- Cabinet relied on a flawed NEB report.

- The federal government did not respond to specific and focused concerns, often leaving unresolved technical work to a later date.

- Canada was biased, closed-minded, and in a conflict of interests.

- Canada failed to disclose important and relevant documents during consultation.

- Canada refused to reconsider the project need in spite of a new economic reality.

- Canada provided insufficient time for First Nations to review the draft CCAR, which was replete with errors.

- Canada was unresponsive to proposals put forward by First Nations on how to accommodate their rights and interests.

- There was no opportunity for First Nations to review the final CCAR.

- The fiduciary duty was breached.

- Rights and title were infringed without engaging in a justification analysis.

- Canada failed to meet legal requirements of CEAA or NEBA.

- Canada failed to recognize governance rights and Indigenous laws.

Stz’uminus First Nation

Stz’uminus territory is located on the east-central coast of Vancouver Island, including Ladysmith Harbour, the Chemainus and Cowichan Rivers, the Salish Sea and the Fraser River. Stz’uminus is a new litigant that was not a party in the Tsleil-Waututh case.

In short, Stz’uminus argues:

“...in its rush to reach its predetermined outcome as quickly as possible, Canada failed to gather necessary information prior to making its decision, failed to share key information that it did have with Stz’uminus, failed to engage in meaningful two-way dialogue and failed to offer appropriate accommodation.”

On May 15, 2019, during the final meeting between Stz’uminus and the Crown, Consultation Director Brett Maracle told Stz’uminus that the impacts of TMX on Stz’uminus rights and interests would be changed from ‘moderate’ to ‘high.’ However, when Stz’uminus was provided with the final CCAR (around the same time cabinet was provided with the document), it listed Stz’uminus’ impacts as ‘moderate.’ Like other First Nations, Stz’uminus had no opportunity to correct or comment on the final CCAR.

Government documents about Stz'uminus' reports were not provided to Stz’uminus at all and the Nation did not become aware of them until after the close of consultation.

Squamish Nation

The Squamish Nation is a Coast Salish Nation whose territory includes Burrard Inlet, English Bay, Howe Sound, the Squamish Valley and north to Whistler.

Canada assessed Squamish’s strength of claim as “weak to moderate to strong,” an assessment that Squamish calls “inherently meaningless” and “singularly unhelpful.”

Canada also initially denied the existence of, and later withheld, its internal reviews of expert reports provided by Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh, discussed below. When pressed by Squamish, Canada provided altered copies of those documents.

Tsleil-Waututh Nation

Tsleil-Waututh Nation (TWN) is a Coast Salish Nation whose name means “People of the Inlet.” This name reflects the Nation’s deep geographic, physical, cultural, and spiritual connections to Burrard Inlet. Tsleil-Waututh territory extends from the vicinity of Mount Garibaldi to the north, the 49th parallel and beyond to the south, west to Gibsons, and east to Coquitlam Lake.

Tsleil-Waututh argues that cabinet’s approval of TMX infringes Tsleil-Waututh’s Aboriginal rights and title without consent or justification. Given the substantial record of Tsleil-Waututh’s (and others’) strong claim to title, the justification standard is required.

TWN also argues that Canada breached the Engagement Protocol, which established a Nation-to-Nation engagement where Canada would seek Tsleil-Waututh’s consent.

Similar to Squamish and Stzu’minus, Canada did not initially disclose that it was in possession of peer review documents containing the government’s assessment of Tsleil-Waututh’s expert reports. When Tsleil-Waututh pressed Canada about these documents, the consultation team initially denied their existence, then refused to provide them, and then withheld them until after the unilaterally imposed deadline to close consultation.

When the peer review documents were finally provided, it was apparent that they had been altered. After cabinet approved TMX, four other versions of the peer reviews were provided.

According to Tsleil-Waututh’s application:

“The unaltered versions of the Peer Reviews establish that Canada and TWN's experts are in substantial agreement on a number of key scientific issues requiring further study prior to the Approval.” (Memo of Fact and Law para 81(f))

Ts’elxweyeqw Tribes

The Ts’elxweyeqw Tribes consist of seven Stó:lō bands: Aitchelitz, Skowkale, Tzeachten, Squiala First Nation, Yakweakwioose, Shxwa:y Village and Soowahlie. Their traditional territory – known as S'olh Temexw – includes the lower Fraser River watershed in southwestern British Columbia in and around the Chilliwack River Valley, including Chilliwack Lake, Chilliwack River, Cultus Lake and areas, and parts of the Chilliwack municipal areas.

The Tribes provided 89 recommendations, produced through their Integrated Cultural Assessment of the Project, and filed in the original NEB hearing. These recommendations were provided to the Crown Consultation team, but Canada did not respond until late in Phase III consultation.

Two days prior to the unilaterally imposed deadline to complete consultation, Natural Resources Canada recognized outstanding concerns about 400 Ts’elxweyeqw cultural sites, and stated that they did not have to complete mitigation measures to make an informed decision.

Finally, Ts’elxweyeqw Tribes differ from the other First Nation Applicants in that they have established rights to fish, resulting from the Van der Peet case in the Supreme Court of Canada. In spite of this established right, Ts’elxweyeqw experienced no difference in consultation from other First Nations. There was no substantive consideration of the fact that Stó:lō is an established rights holder, and Canada failed to conduct the justification analysis set out in Sparrow.

Shxw’owhamel First Nation

Shxw’owhamel First Nation is another new Applicant in this round of court challenges. Shxw’owhamel is a part of the Stó:lō Nation, and part of the Tiy’t Tribe, whose territory is located around Hope, BC.

Shxw’owhamel was previously in favour of TMX, but concerns about Trans Mountain’s reluctance to re-route the pipeline in order to protect an ancient village site that includes sacred and historic pit house sites caused a change of heart. The current route will destroy Shxw’owhamel pit house sites. Further archaeological investigation was not completed before project approval, meaning there are likely many other sites at risk.

Like the other First Nations Applicants, Shxw’owhamel argues that consultation was “unnecessarily aggressive” and did not allow for meaningful two-way dialogue. Shxw’owhamel was denied a culturally appropriate forum for the process, and the initial draft Memorandum of Understanding was “a low bar with factual inaccuracies.”

Coldwater Band

Coldwater Indian Band is one of 15 bands comprising the Nlaka’pamux Nation, whose territory includes the Lower Thompson River area, the Fraser Canyon, the Nicola and Coldwater Valleys, and the Coquihalla area. Coldwater’s reserve is located in the Coldwater River valley, just south of Merritt, BC.

The central issue for Coldwater has consistently been the threat of the pipeline route to its aquifer, which is the only source of water for 90% of the Coldwater reserve. Trans Mountain re-routed around the Coldwater reserve to avoid requiring consent, selecting a route that threatened Colwater’s aquifer. Trans Mountain would not consider route alternatives that would avoid the aquifer.

Coldwater also argues that Canada has a fiduciary obligation to protect Coldwater’s interests because the pipeline will impact the reserve. Recently, Coldwater won an important case around the fiduciary duty with the original pipeline, which crosses the reserve and is currently causing problems for residents due to incomplete cleanup and remediation, following a leak in 2014.

During Phase III, Canada’s consultation team recognized and acknowledged Coldwater’s concerns regarding their aquifer, describing outstanding hydrogeological information as “essential.” Canada initially agreed to conduct a joint study with Coldwater, but did not take meaningful steps towards starting that study.

Instead, Canada proposed a condition after the unilaterally imposed deadline to end consultation that, in Coldwater’s view, made the situation even worse. Specifically, NEB Condition 39 requires the completion of a hydrogeological assessment six months prior to construction. Canada’s proposed amendment introduces a new deadline of December 31, 2019, which Coldwater argues is not enough time to complete the study. This proposal, argues Coldwater, is not accommodation, but a commitment for more process bound by new, arbitrary deadlines, making it even worse than the original NEB condition.

Upper Nicola Band

Upper Nicola Band is a member community of the Sylix (Okanagan) Peoples, whose reserve is located near Douglas Lake, east of Merritt and south of Kamloops.

Canada did not recognize Upper Nicola’s unextinguished Indigenous law, the Sylix law of tmixwlaxw, which governs the stewardship of Sylix Territory by Upper Nicola and Sylix people.

Upper Nicola argues that key information required to make an informed decision remains outstanding, regarding a number of issues including cumulative effects; impacts on watercourse crossings; diluted bitumen spills and spill response; impacts on groundwater; geohazard and seismic implications; and specific issues related to the Kingsvale Transmission line – an electrical transmission line planned as a part of the project that impacts Upper Nicola’s rights.

During Phase III consultation, Upper Nicola expressed “ongoing concern that the same failed process from Phase III consultation was starting to emerge; that Canada was engaged in an exercise of ticking off boxes for sufficient Crown consultation.” (Memorandum of Fact and Law, para 38)

Stk'emlupsemc te Secwepemc Nation

Stk’emlupsemc te Secwepemc (SSN) is comprised of the Skeetchestn Band and Tk’emlups Band, also known as the ‘Kamloops Division’ of the Secwepemc Nation around the confluence of the Thompson and Fraser rivers. Secwepemc traditional territory (Secwepemcul'ecw) stretches from the Columbia River valley along the Rocky Mountains, west to the Fraser River, and south to the Arrow Lakes.

SSN argues that the NEB report was so flawed that it was not a report that cabinet could rely on, adding the failure to review the impact of the endangered Thompson River steelhead trout.

One of SSN’s primary concerns is the risk to the sacred site at Pípsell (aka Jacko Lake). SSN has applied its unextinguished Indigenous laws to protect this site from the Ajax mine. TMX similarly threatens the site.

When SSN proposed a route change at the NEB’s specific route hearing, Trans Mountain argued that SSN had not provided sufficient evidence of a better route that did not threaten Pípsell. As SSN argues: “...it is an unfair burden to place on First Nations to argue against a well-funded pipeline company as to a better route for the pipeline corridor.” (Draft Notice of Application for JR, para 101)

In other words, Trans Mountain’s expectation that SSN would do the company’s job is not meaningful accommodation, nor does it uphold the Honour of the Crown, especially when the federal government did not participate in the hearings and would not consider re-routing the pipeline during Phase III.

SSN’s experience in consultation caused them to argue in their Draft Application for Judicial Review:

“The Crown has not acted in accordance with the Honour of the Crown and/or its fiduciary duties to the SSN and indeed, has acted no differently than the proponent who constructed the existing pipeline in the 1950s.” (at Para 29(f)(iv))

Conclusion

Reviewing the eight First Nations Applications for Leave quickly reveals a number of patterns and common experiences, although each Nation raised unique issues and experiences as well. The government’s one-size-fits-all approach to consultation undermines the requirement to engage with each Nation’s specific and focused interests and concerns individually, in a manner that takes into account historical context and cumulative effects.

Together, the legal challenges and arguments raised by Indigenous applicants amount to significant risk that Trans Mountain’s recent approvals will once again be quashed. They suggest that Canada was once again aiming for the floor on consultation, and raise questions about whether the government was simply looking to tick the appropriate boxes before arriving at its predetermined outcome.

So what’s next? The Federal Court of Appeal still has to grant leave (or permission) to hear the cases. Canada did not take a position on whether these cases were arguable, with the exception of the climate strikers. In the meantime, the NEB has weakened some of its conditions at Trans Mountain’s request in order to allow construction at the Burnaby, Edmonton and Sumas terminal sites. Without an injunction or other court order, construction may continue.

Finally, two of the First Nations Applicants (SSN and Shxw’owhamel) had previously filed Aboriginal title cases which could add a whole other dimension to the Trans Mountain saga.

You can support the First Nations legal challenges by donating or organizing a fundraiser at www.pull-together.ca.

A special shout-out to our summer law students/interns who helped review the thousands of pages of legal documents for this blog: Jessie Schwarz, Isabelle Lefroy, Whitney Vicente, Chris Mottershead, and Justin Fishman.

Top photo: First Nations announce the new round of TMX legal challenges at a press conference in July 2019. (Photo: Eugene Kung)