A new BC law promises to speed up approvals for renewable energy projects. But in practice, it’s designed to power LNG exports and mining – and it could gut environmental oversight in the process.

On July 1, 2025, the Renewable Energy Projects (Streamlined Permitting) Act (REPSPA) came into force in BC. This statute was introduced this spring as Bill 14, alongside Bill 15 (the Infrastructure Projects Act) as part of a package of legislation that the BC government says is designed to fast-track approvals of various projects in response to tariff threats and economic uncertainty.

While the Infrastructure Projects Act is more wide-reaching, the REPSPA is narrowly focused: its stated aim is to “streamline” the review and approval of renewable energy projects, starting with wind and solar power projects, alongside BC Hydro’s proposed North Coast Transmission Line (NCTL) and related transmission projects.

While facilitating the development of renewable energy capacity is a laudable goal, the express purpose of the North Coast Transmission Line is to dramatically increase the availability of electricity to meet the rapidly-growing demands of BC’s growing liquefied natural gas (LNG) export industry, as well as mining projects and other industrial development on the North Coast. Meanwhile, the wind and solar projects that this legislation will facilitate are needed to supply the energy demanded by the LNG industry. Furthermore, this loosening of the regulatory framework comes alongside massive public investments that aim to make LNG economically viable through electrification – undermining BC’s climate goals and previous efforts to eliminate fossil fuel subsidies.

What does the Renewable Energy Projects (Streamlined Permitting) Act (REPSPA) do?

The main functions of the REPSPA are:

- to place renewable energy projects under the regulatory authority of the BC Energy Regulator, as a “one-window” regulator replacing all government agencies that would otherwise be responsible for permitting and inspection of the projects; and

- to exempt wind power projects, the North Coast Transmission Line and other related transmission line projects from BC’s environmental assessment process.

Initially, the REPSPA only officially applied to the NCTL and the nine wind power projects selected by BC Hydro in its 2024 call for power, but the government can add other renewable energy and transmission line projects to the regime by passing regulations to that effect. A regulation has already been passed expanding the REPSPA to cover all wind and solar projects, and to add the North of Terrace Transmission Line and the North Montney Transmission Line to the statutory regime. Statements from the government suggest that all renewable energy projects may eventually be under the BC Energy Regulator’s purview.

The BC Energy Regulator: A Troubled History

Prior to the REPSPA, renewable energy projects – like most industrial projects in the province – were subject to regulatory oversight by various government agencies, such as the Ministry of Environment and Parks (for water and other environmental issues), the Ministry of Forests (for cutting permits), and the Ministry of Tourism, Arts, Culture and Sport (for archaeology permits).

Now, these projects will be overseen by the BC Energy Regulator, which will have authority over all of these subject areas. That authority will include assessment and permitting, inspection of permitted facilities, and enforcement where infractions are found.

The BCER, formerly known as the Oil and Gas Commission, was established in 1998 to be a one-window regulator for the petroleum industry in BC. In 2022, its jurisdiction was expanded to include hydrogen, ammonia, methanol, and carbon capture and sequestration. Unlike most provincial regulators, the BCER is a Crown corporation that receives all of its funding from fees and levies collected from the industry it regulates – a funding model that critics have said may make the regulator beholden to the industry.

The BCER has long been the subject of criticism and skepticism for its lack of transparency and apparent lax approach to regulation. Earlier this year, a joint investigation by the Narwhal and the Investigative Journalism Foundation highlighted the scope of the problem: in unpublished BCER inspection records for 2017 to 2023 obtained through freedom of information requests, the journalists found more than 1,000 instances where inspectors noted serious deficiencies in their notes, but officially reported the sites as “compliant” with provincial regulations. The concerns that inspectors documented (but did not flag for public reporting or further enforcement) appear to include serious and imminent threats to human health or the environment, some of which had been ongoing for several years.

The Narwhal also reported on how the BCER gave a large-scale exemption from regulatory requirements to 4,300 pipelines operated by Canadian Natural Resources Ltd. – which may otherwise have been the subject of significant fines for failing to comply with decommissioning deadlines. The regulator kept that fact secret from the public for five years, until it was forced to disclose it in response to the Narwhal’s freedom of information request.

A transition of regulatory authority to the BCER likely means that the regulation of renewable energy projects will be less transparent and with fewer opportunities for public engagement. The BCER’s track-record of secretive and lax enforcement of the oil and gas industry also presents significant concerns that the regulator will be able and willing to hold renewable energy project proponents accountable for non-compliance with provincial regulatory standards.

Bypassing Environmental Assessments

Under the REPSPA, many major energy projects will no longer go through BC’s environmental assessment process – meaning less transparency, fewer voices at the table and weaker oversight.

Since at least 2023, BC Hydro has been lobbying the BC government to exempt the North Coast Transmission Line from the requirement for a provincial environmental assessment. Under the new law, that exemption has now been granted for the NCTL as well as the North of Terrace Transmission Line and the initial set of nine wind power projects. It can also be extended by regulation to other related transmission lines and any wind power projects designated by the government.

Details of the new review process for these projects remain sparse, and no information has yet been published on the regulator’s approach to the NCTL and other transmission lines. So far, a policy document published by the BCER suggests that wind projects will now be subject to a much narrower and less transparent review. In place of the Environmental Assessment Office’s public registry, where anyone can submit comments directly to the regulator for consideration, the BCER proposes to delegate all public consultation to the project proponent. The BCER also proposes to require consultation with only those who are most directly affected by the project.

This change would prevent independent experts and community groups from bringing unforeseen risks to the regulator’s attention – and even those directly-affected individuals permitted to participate will have their input filtered through the project proponent, with no opportunity to engage directly with the regulator.

Furthermore, the abbreviated process proposed by the BCER provides limited opportunity for assessing cumulative effects, with no evaluation of such effects being required of the project proponent. The cumulative effects connected to a renewable energy or transmission line project that is used to electrify LNG operations are potentially enormous in scope, and it’s not clear that the BCER’s review process will assess such effects properly or at all.

Electrifying LNG and BC’s Climate Goals

For years, the BC government has been facilitating and promoting the development of an LNG export industry on BC’s coast as a way to stimulate economic growth. Natural gas, produced in northeastern BC, will be piped to the coast for export overseas. In order to make shipping feasible, the gas is condensed into a liquid by chilling it to -162°C at coastal liquefaction facilities.

LNG liquefaction is highly energy intensive. The power for this process can come from one of two sources: burning some of the incoming natural gas, or electricity from the provincial power grid. The first phase of the LNG Canada plant being built in Kitimat is designed to use natural gas turbines for compression, while all other BC LNG facilities under construction or in the approval process plan to use grid power.

In addition to the emissions that can come directly from gas-powered compression, LNG expansion also means additional upstream emissions (emissions that occur in the process of extracting the gas from the ground) – primarily from methane and carbon dioxide releases from underground formations, flaring and gas-powered infrastructure. The higher the demand for gas by LNG exporters, the greater the upstream emissions.

According to a 2023 report by the Pembina Institute, bringing only the LNG Canada Phase 1 and Woodfibre LNG plants into operation (the two projects that were approved at that time) without significant infrastructure and policy changes would result in BC blowing through the CleanBC 2030 target for greenhouse gas emissions from the oil and gas sector, hitting almost double the emissions target. If all proposed projects were approved and built, emissions would rise to more than triple the target.

The only way for BC to build an LNG export industry while meeting its sector targets for emissions, Pembina found, is to aggressively electrify the industry (both at terminals and in upstream production) while clamping down on fugitive emissions and flaring – and even then, the industry would need to invest in carbon offsets.

How much electricity does the oil and gas sector need in order for BC to meet its climate targets? Pembina calculated that fully electrifying all current and proposed projects and partially electrifying the upstream production required to support them would require a staggering 42,700 GWh/year, or the equivalent of 8.4 Site C dams.

This puts the BC government in a tricky place: it has already approved projects that will cause it to massively overshoot its climate goals if not electrified, but BC Hydro doesn’t have enough power or transmission capacity to electrify them.

Enter the North Coast Transmission Line and BC Hydro’s latest calls for an additional 10,000 GWh/year of power from independent producers, the first batch of which are explicitly included in the REPSPA. These projects represent a massive public investment in generation and transmission capacity to provide cheap electricity to facilitate the expansion of BC’s oil and gas industry. On top of the unprecedented $16 billion price tag for the Site C dam and a projected $3 billion for the NCTL, the BC government recently announced a $200 million subsidy for transmission infrastructure to electrify the Cedar LNG project – matched by a recent $200 million subsidy from the federal government.

The North Montney Transmission Line, which was added to REPSPA by regulation after the bill was passed, will be key to the electrification of upstream gas production in northeast BC. The North of Terrace Transmission Line, also added by regulation, will bring more power to an area of northwestern BC rich in mineral interests.

While the legislation makes no mention of LNG, the Renewable Energy Projects (Streamlined Permitting) Act appears to be the latest in a suite of efforts by the provincial government to make it easier and cheaper for oil and gas companies to profit from BC’s natural resources. The loose framework set out by the law still leaves open the possibility that the BC Energy Regulator could apply strict environmental standards and a rigorous review process, but neither they nor the government have earned the benefit of the doubt.

West Coast does not support the exemption of these projects from environmental assessment, but if review is to occur by the BCER, the review process established should be transparent, offer opportunities for meaningful public participation and independent expert evaluation of impacts, provide mechanisms to fully assess the cumulative effects of LNG expansion, and prioritize the free, prior, and informed consent of affected First Nations title and rights holders.

Despite the challenges posed by this new legislation, public feedback is critical to ensuring that the new regulatory process – still under development by the BCER – has the right priorities. While the first phase of the BCER’s public engagement process has officially closed, it is still accepting feedback on its draft policy intentions for renewables. An additional engagement opportunity is promised for Fall 2025, as it develops more specific regulatory proposals.

Check out our Submission Regarding Policy Intentions for the Regulation of Renewable Energy Projects.

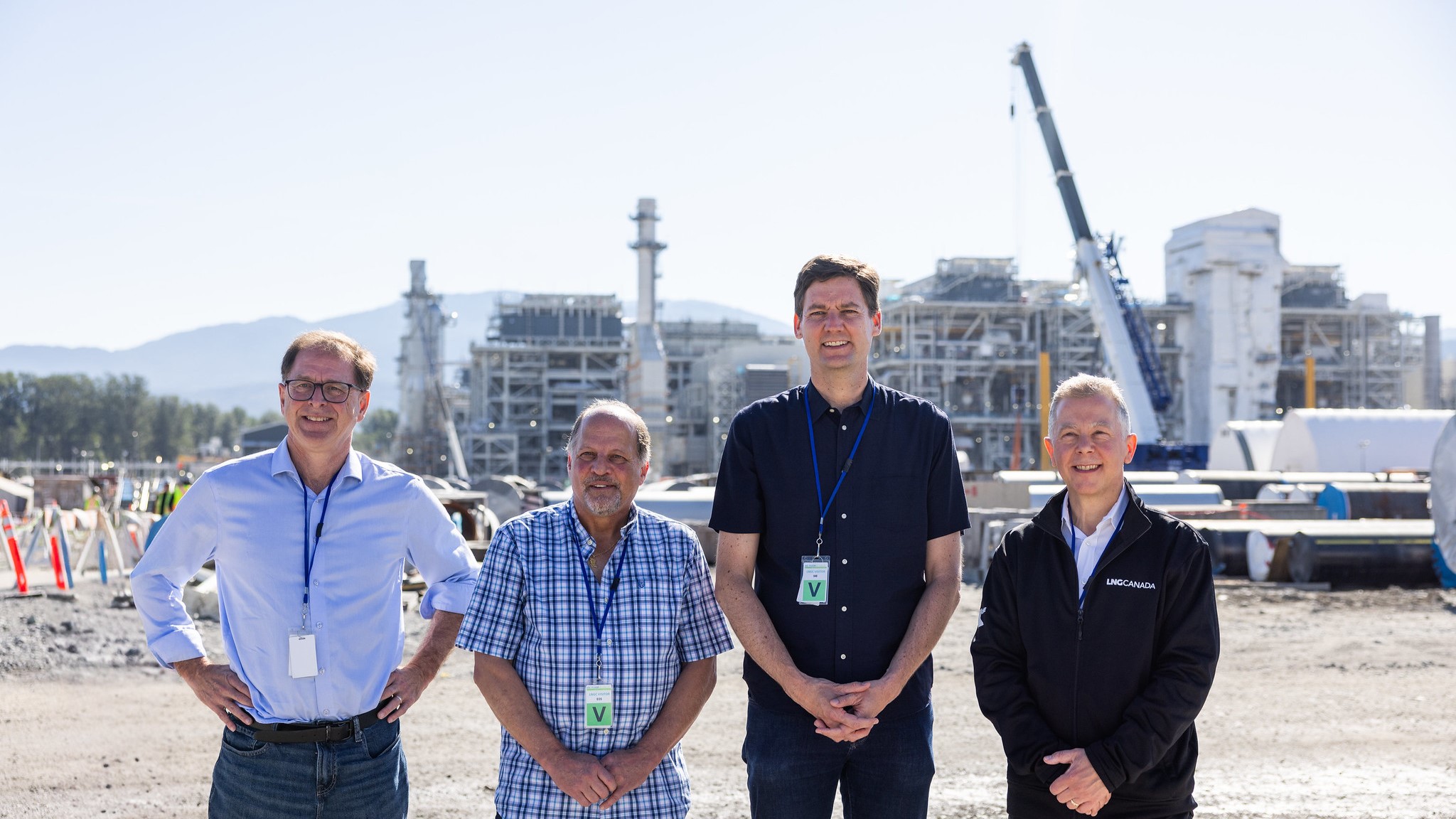

Top photo: BC Premier Eby and Energy Minister Adrian Dix visit the LNG Canada facility. BC’s Bill 14 – the Renewable Energy Projects (Streamlined Permitting) Act – appears to be primarily intended to electrify LNG plants like LNG Canada / Photo: Province of BC via Flickr Creative Commons