Living at the edge of the biodiversity-rich and vulnerable Salish Sea, we welcomed the news of one and a half billion dollars to protect Canada’s oceans and coasts, an investment of a scale we’ve not seen for decades. It was a mixed blessing: Prime Minister Trudeau and Minister of Transportation Marc Garneau’s visit to Vancouver to announce the Oceans Protection Plan focused on marine safety, and was widely viewed as the prelude to the approval of the Kinder Morgan Trans Mountain Expansion pipeline and tankers proposal that followed.

At West Coast we’re buckling down to protect the Salish Sea, the global atmosphere, and future generations – a journey that will take us through 2017 and likely well beyond. My colleague Eugene Kung has described the new phase of efforts to stop the Kinder Morgan expansion. At the same time, we are also looking at opportunities to achieve better coastal management, generally. Even without Kinder Morgan there are gaps to fill.

A new era of coastal management in Canada?

The federal Oceans Protection Plan is launching a new (and much-needed) agenda – coastal habitat planning with federal participation. According to the backgrounder from the Prime Minister’s Office:

…investments will be made in the preservation and restoration of vulnerable coastal marine ecosystems. Funding will support the establishment of coastal zone plans and identify restoration priorities on all three coasts. Habitat restoration projects will engage Indigenous groups, resource users and local groups and communities.

BC’s north and central coast has already benefited from marine and coastal planning through a partnership between First Nations and the Province (see my colleague Linda Nowlan’s articles on the Marine Action Planning Partnership, MaPP and outcomes here and here). The federal government walked away from that process in the early stages, meaning that important pieces of the jurisdictional puzzle that belong to the federal government – such as shipping, marine protection and fisheries – are missing. It isn’t immediately clear if and how this new federal initiative will support implementation of the MaPP plans, although it is certain that federal engagement and legal protection is needed to ensure the plans meet their full potential.

On the south coast, and in particular around the Salish Sea, we currently lack any coordinated process (at least on the Canadian side) to protect coastal and marine ecosystems. This type of coordination is desperately needed in order to manage and monitor the ongoing and cumulative effects of human activities, such as industrial and residential development, shipping, and waste disposal (both legally permitted and not).

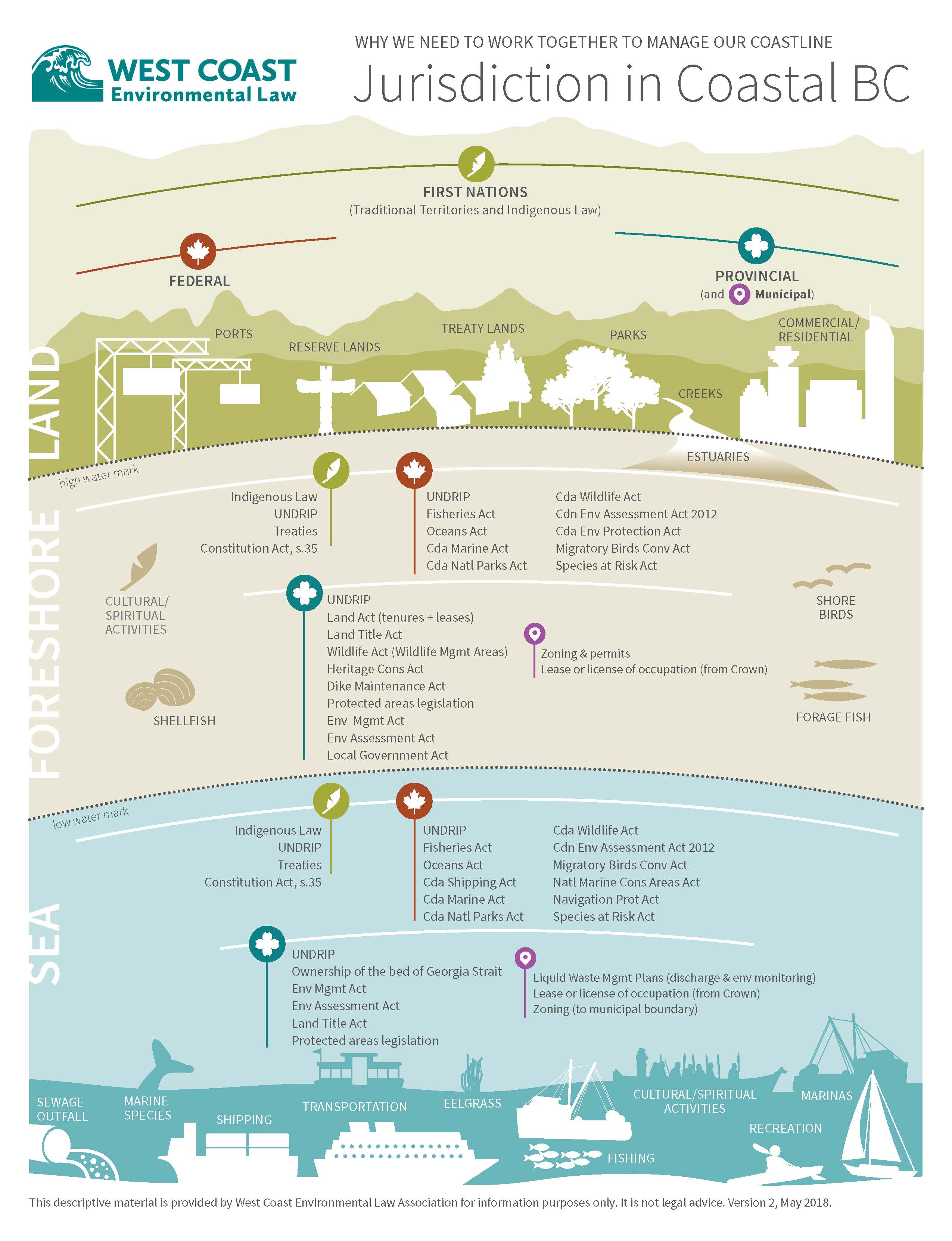

Convoluted coastal jurisdiction explained

There are so many different legal authorities and regulations that have some bearing on the shoreline and the marine environment that it would probably take several blogs to describe them properly. To save everyone some time, we prepared this infographic to help explain the very complicated regulatory environment in coastal BC. If you are thinking that the infographic doesn’t show the relationship between the different statutory and other authorities, you would be correct, but be advised that in many cases there isn’t a relationship. With the exception of First Nations, governments do not approach the management of the coast in an integrated way.

Instead, we regulate the shoreline according to uses, for the most part, and in a way that is designed to facilitate those uses without huge regard for the shoreline itself. For example, much of the foreshore in BC that isn’t controlled by federal port authorities is provincial Crown land, administered under the Land Act. If you want to carry out an activity in the foreshore, you must get permission from the Crown, likely in the form of a licence or lease. There is a whole sheaf of specific Crown land policies that explain how to do this, ranging from docks to aquaculture operations.

These licences and leases are granted up and down the coasts of BC with no consideration of cumulative effects. At the same time, for the past 100 years we have concentrated industrial and commercial development along the water and at the mouths of rivers, where it was flat and convenient for shipping, and modified the shorelines accordingly with walls and fill. Sewage outfalls were constructed to drain waste – some treated, some not – into coastal waters.

There was no intention to harm coastal ecosystems, but there was little consideration given to protection, either. The results have been devastating: in the Burrard Inlet, more than 93% of the coastal wetlands that existed until colonization have been lost.

Environmental oversight needed for the Salish Sea

Past attempts, not entirely successful, to address the lack of environmental oversight on the south coast include the Fraser River Estuary Program (FREMP) and the Burrard Inlet Environmental Action Program (BIEAP). For a number of years, until the previous federal government dissolved them in 2013, these programs coordinated environmental approvals for activities through a referral system, and also sponsored some environmental research and monitoring activities.

Neither FREMP nor BIEAP had any independent regulatory powers, and their resources for planning and research were limited, but they did at least provide a common point of reference for environmental issues in the region.

As climate change speeds up and sea level rises, the gaps in our coastal and marine environmental protection and management regime grow more glaring. We have little data, for example, about the vulnerability of Salish Sea coastal ecosystems to climate change. Nor do we have comprehensive mapped information about sediment transportation mechanisms, sometimes referred to as “drift cells” – the interaction among wind, waves and shorelines that shapes patterns of accumulation and erosion along the coast. This information becomes even more important to understand as local governments consider measures to protect waterfront developments from sea level rise – measures that may interfere with natural physical coastal processes.

By contrast, coastal management at the scale of drift cells is considered so basic in New South Wales, Australia that the new Coastal Management Act 2016 provides a schedule listing coastal drift cells and the local governments responsible for managing them. The legislation further requires local governments that have shorelines in a common drift cell to consult each other in coastal planning (section 16 of the Act).

Benefits of coastal protection

Pacific sand-lance. Photo: Mandy Lindeberg

From an ecological perspective, the foreshore is essential habitat for forage fish like the surf smelt and Pacific sand lance, which form a critical part of the marine food web that supports both salmon and orcas. Forage fish biologist and champion Ramona de Graaf recently detailed concerns around forage fish and the lack of protection for their habitat in submissions to the Fisheries Act review process.

Not only do we need to restore the habitat provisions in the Fisheries Act, we must do a better job of assessing habitat. A recent study confirmed that understanding forage fish habitat function requires investigation at the scale of the drift cell, and it follows that effective coastal management must also take this into account.

Living shorelines and ecologically engineered coastal infrastructure can also reduce flood and coastal erosion risks. These measures are already used in a number of countries, such as the US, with support from the US President. Even communities faced with serious coastal flood risks are asking questions about “softer” approaches to flood protection, as a recent community engagement process in Surrey demonstrated.

Salish Sea solutions

Many countries have integrated coastal management planning and regulation – the US, Australia and New Zealand all provide accessible examples. Given the gaps and shortcomings in our current approach, it is time that BC and Canada took serious stock of the problems with the current jumble of environmentally ineffective regulations and considered integrated, legally binding coastal plans as a partial solution.

Along with the Oceans Protection Plan, the federal government also announced that it will reinstate a regional planning forum in the Lower Fraser region to replace FREMP and BIEAP. While this is encouraging news, we need to aim higher than reinstating bodies whose main function is to coordinate a bunch of weak environmental protection mechanisms. The Tsleil-Waututh Nation has already stepped forward with a renewed vision for environmental management in the Burrard Inlet. With political and community leadership, there can be similar inspiration applied in other parts of the Salish Sea.

With these solutions in mind, we hope that 2017 will bring some fresh hope and love for our beautiful, but troubled, Salish Sea.

Top photo: Environmental oversight is needed to preserve the coastline of the Salish Sea from industrial, shipping and other human impacts / Deborah Carlson.