December 1st marked a turning point in the effort to protect the Pacific coast and the watersheds that we all depend on from the threat of oil spills. For the first time, First Nations from the north coast, the south coast, and the Interior gathered together to declare, in solidarity, that tar sands pipeline and tanker projects are banned in their respective territories. Tar sands oil tankers and pipelines are now banned, as a matter of Indigenous law, across the entire land mass of British Columbia, and in an unbroken swath along BC’s coast, reaching from the U.S. border all the way to the Arctic Ocean. Wherever these Nations have their territories, they have recognized how they are all connected by water and that the proposed pipelines and tankers threaten all of them.

December 1st marked a turning point in the effort to protect the Pacific coast and the watersheds that we all depend on from the threat of oil spills. For the first time, First Nations from the north coast, the south coast, and the Interior gathered together to declare, in solidarity, that tar sands pipeline and tanker projects are banned in their respective territories. Tar sands oil tankers and pipelines are now banned, as a matter of Indigenous law, across the entire land mass of British Columbia, and in an unbroken swath along BC’s coast, reaching from the U.S. border all the way to the Arctic Ocean. Wherever these Nations have their territories, they have recognized how they are all connected by water and that the proposed pipelines and tankers threaten all of them.

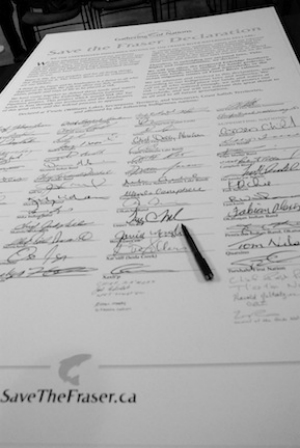

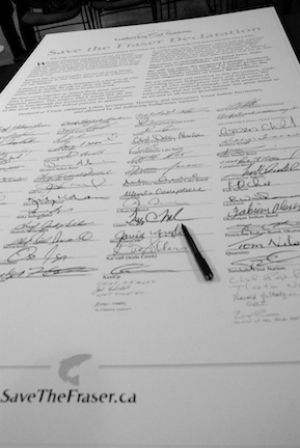

West Coast was invited to witness a special ceremony to rededicate the Save the Fraser Declaration on its first anniversary, hosted by the Yinka Dene Alliance in Coast Salish Territories in downtown Vancouver. The ceremony brought together the signatories of the Coastal First Nations Declaration and signatories of the Save the Fraser Declaration, to declare that their commitment, as an exercise of their authority over their lands and waters and their will to protect them, is stronger than ever. Several new Nations signed onto the Save the Fraser Declaration, and it was explicitly recognized that the Declaration not only bans the proposed Enbridge pipeline and tankers in the north, but also the proposed Kinder Morgan pipeline and tanker expansion, which would see a massive increase in oil tanker traffic through the port of Vancouver, the Salish Sea, and through the southern Gulf Islands and the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

“North or south, it makes no difference,” said Chief Jackie Thomas, of the Saik’uz First Nation, at the ceremony and press conference on Thursday morning. “First Nations from every corner of B.C. are saying absolutely no tarsands pipelines or tankers in our territories.”

The participation of First Nations from the south coast in the ceremony, united in solidarity with allies from the north and along the Fraser watershed, was a crucial new development in the long-running drive to protect the coast from oil spills. The ceremony was opened with a welcome from the Tsleil-Waututh Nation, whose traditional territories include Kinder Morgan’s Burnaby oilport – which is directly across from their home community on Burrard Inlet. The Tsleil-Waututh recently announced that they oppose the expansion of the Kinder Morgan pipeline and the associated expansion of tanker traffic. The day after the Save the Fraser ceremony, Tsleil-Waututh sponsored a resolution at the chiefs’ assembly of the First Nations Summit, an organization with most BC First Nations as its members, to oppose the Kinder Morgan project. The Musqueam Nation, an original signatory of the Save the Fraser Declaration whose territories would be deeply affected by oil tanker traffic on the south coast, also sent a representative to join the ceremony and stand in solidarity with the First Nations from every region of the province that gathered together.

The participation of First Nations from the south coast in the ceremony, united in solidarity with allies from the north and along the Fraser watershed, was a crucial new development in the long-running drive to protect the coast from oil spills. The ceremony was opened with a welcome from the Tsleil-Waututh Nation, whose traditional territories include Kinder Morgan’s Burnaby oilport – which is directly across from their home community on Burrard Inlet. The Tsleil-Waututh recently announced that they oppose the expansion of the Kinder Morgan pipeline and the associated expansion of tanker traffic. The day after the Save the Fraser ceremony, Tsleil-Waututh sponsored a resolution at the chiefs’ assembly of the First Nations Summit, an organization with most BC First Nations as its members, to oppose the Kinder Morgan project. The Musqueam Nation, an original signatory of the Save the Fraser Declaration whose territories would be deeply affected by oil tanker traffic on the south coast, also sent a representative to join the ceremony and stand in solidarity with the First Nations from every region of the province that gathered together.

Enbridge responded with a lot of the same public relations spin that they’ve been using all along, including vague statements that they have a lot of support, and deflecting the issue by stating that their pipelines won’t cross the Fraser River. The point of the Declaration, ignored by Enbridge’s statements, is that the proposed pipeline crosses through the Fraser watershed, and in particular, several major salmon rivers that flow into the Fraser.

The day after the Dec 1st declaration, Enbridge tried something new, which was to announce that at long last, they had support from a First Nation that had signed onto their project in a financial deal, in an announcement that appeared to be rushed out the door as a PR effort in response to the massive announcement from First Nations the day before. We cannot comment on the ensuing developments, except to say that the endorsement did not work out the way that Enbridge would have hoped.

Regardless of any new deal that Enbridge may announce now, the fact is that more than 130 First Nations governments in western Canada have firmly declared that they do not support the Enbridge Northern Gateway Project and that they will not support such projects anywhere in the traditional territories of opposed First Nations; as a result, there is unprecedented unified opposition to both the Enbridge and the Kinder Morgan pipeline and tanker projects.

These Declarations matter – not only politically, but also as a matter of law. As I have said in a previous post about the Yinka Dene Alliance’s actions at the Enbridge annual shareholders meeting in Calgary in May 2011, the decisions of First Nations expressed in the Save the Fraser Declaration, and the Coastal First Nations Declaration, are an exercise of the constitutionally-protected Aboriginal Title over the lands and waters of their territories. As such, they are arguably protected in international law – not only through the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, but by other agreements to which Canada is a party such as the American Declaration on the Rights and Duties of Man and legal decisions interpreting them (see our legal analysis of the Coastal First Nations Declaration, at page 2).

These Declarations matter – not only politically, but also as a matter of law. As I have said in a previous post about the Yinka Dene Alliance’s actions at the Enbridge annual shareholders meeting in Calgary in May 2011, the decisions of First Nations expressed in the Save the Fraser Declaration, and the Coastal First Nations Declaration, are an exercise of the constitutionally-protected Aboriginal Title over the lands and waters of their territories. As such, they are arguably protected in international law – not only through the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, but by other agreements to which Canada is a party such as the American Declaration on the Rights and Duties of Man and legal decisions interpreting them (see our legal analysis of the Coastal First Nations Declaration, at page 2).

While it cannot be predicted how Canada’s courts or international bodies would deal with this particular situation, or how the doctrine of “free, prior and informed consent” will be applied by those courts, it is clear that one or more First Nations may take steps to enforce these declarations under their own laws, through the Canadian courts, and/or through legal action at the international level. The result would be a highly volatile legal situation and a strong probability of litigation by one or more First Nations that could delay or potentially derail the Enbridge Northern Gateway Pipelines project.

Already the Enbridge review hearings have been delayed by a year, in part because of the sheer numbers of intervenors and individuals who legitimately want to have their say about this project. The multiplication of legal risks from the deeply entrenched opposition – as demonstrated by the unequivocal Declarations against the project by many different affected First Nations – means there is an extremely volatile legal situation that could ultimately derail this project. The massive First Nations opposition, combined with the overwhelming opposition from the rest of the population, means that it’s unlikely that Enbridge’s tankers will see the light of day, and that Kinder Morgan faces an uphill battle to expand the oil port in Vancouver.