Marine protected areas, or MPAs for short, are areas of the ocean that provide protection from harmful human activities and exploitation. Decades of scientific research documenting the effects of MPAs prove that they are effective tools for marine conservation, for rebuilding marine biological diversity, and for managing marine resources. Consequently, MPAs are also expected to maintain and enhance marine ecosystem services – the many and varied benefits people obtain from the marine environment.

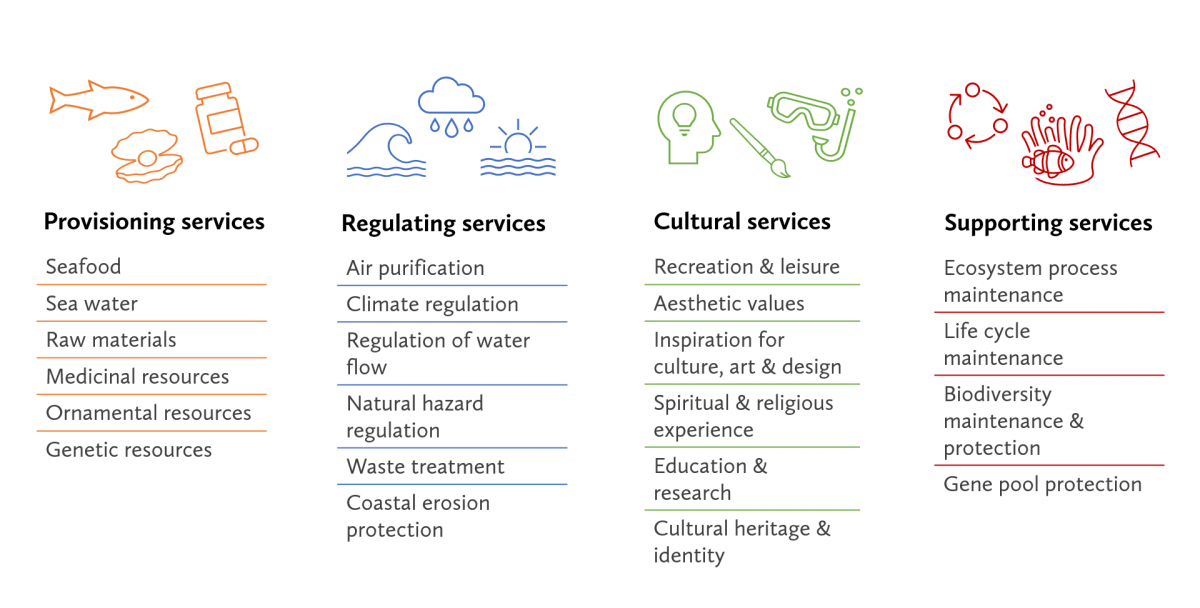

Marine ecosystem services include provisioning services, cultural services, regulating services, and supporting services, all of which contribute to human well-being.

- Provisioning services are the tangible, harvestable goods obtained from marine ecosystems, such as seafood and medicinal resources.

- Regulating services refer to the benefits obtained from the regulation of ecosystem processes, including the regulation of climate, water, and oxygen production.

- Cultural services are the non-material benefits that arise from the interactions between people and marine environments, such as aesthetic experiences, spiritual enrichment, and recreational activities.

- Supporting services underpin almost all other ecosystem services the ocean provides to us, from habitats for the fish we eat to the maintenance of genetic diversity.

Marine ecosystem services (adapted from Millennium Ecosystem Assessment)

Our ability to tap into the human benefits of marine ecosystem services strongly depends on healthy oceans. MPAs can help safeguard these benefits by maintaining or enhancing ocean health.

According to a global review, most studies that have investigated societal impacts of MPAs have focused on how they contribute to communities’ economic well-being, such as catch rates and income (see our previous blog for more on this). Comparatively, non-monetary aspects of human well-being (e.g., emotional, health, and cultural benefits) have received little attention, in large part due to challenges in quantifying and studying them.

Despite being understudied, these aspects of human well-being are important in how people perceive, support or interact with MPAs. Given that social acceptance can greatly influence the success of conservation initiatives, raising awareness about how marine protection can affect aspects of human well-being – both economic and non-economic – and how the benefits for people can be maximized, will help promote successful conservation into the future.

Here we bring to light some lesser-known benefits of MPAs that relate to recreation and leisure, mental and emotional health, and non-use values.

- Recreation and leisure

MPAs do not always mean that people are prohibited from using or accessing a particular area; in fact, many MPAs allow recreational activities to continue as previously. Recreational activities permitted within MPAs may include scuba diving, snorkeling, recreational fishing, surfing, wildlife watching, sailing and boating. These nature-based activities play an important part in maintaining physical, mental and emotional health. In many situations, these activities and the personal benefits gained from them are the most important values that people associate with nature.

MPAs can help maintain aspects of nature that draw people in and result in a connection with nature: things like good water quality, scenic beauty, and an abundance and diversity of animals and plants. They can even create new opportunities for recreation and leisure, as well as tourism.

Establishing MPAs can benefit recreational users in various ways, such as aesthetic appreciation or opportunities for spiritual experiences and artistic inspiration. It can also benefit nearby communities by maintaining or creating new income opportunities for nature-based tourism. For instance, the establishment of Tonga Island Marine Reserve in New Zealand increased the number of visitors to the area, resulting in more jobs and new businesses (e.g., taxi service and hotels) for nearby communities. The number of kayak companies increased from two prior to the establishment of the marine reserve, to 13 currently.

"MPAs do not always mean that people are prohibited from using or accessing a particular area; in fact, many MPAs allow recreational activities to continue as previously."

- Mental and emotional health

Coastal and marine areas provide therapeutic and restorative places for promoting well-being and mental health. Emerging research suggests MPAs can amplify positive benefits people gain from their interactions with nature.

A 2017 UK study found that visits to nature, especially those to protected areas and coastal environments, were associated with greater feelings of relaxation and refreshment, along with stronger emotional connections to the natural world. Another study in the UK documented similar subjective well-being benefits from recreational divers and anglers, including gains in place identity and therapeutic value.

And it’s not just visitors who benefit – similar benefits have been observed in those involved in MPA management. For example, Australian volunteers engaged in an MPA monitoring program reported feelings of enjoyment and personal satisfaction through their contributions, along with other positive mental and emotional health benefits. In a study from the Philippines, locals engaged in MPA management identified a wide range of positive personal impacts, from a sense of pride to a greater motivation to preserve fishing opportunities and aesthetic experiences for their children and grandchildren.

- Non-use values

Ecosystem services provided by MPAs include ‘non-use’ values – the value that people derive from MPAs independent of any present or future use. These values are often difficult to measure and include bequest, existence, and option values.

Bequest values arise from wanting to preserve an ecosystem service for future generations. By protecting natural, historic, and cultural resources, people both near and far from MPAs can feel better knowing that a particular species or habitat is being protected, or that a cultural or historic treasure is being preserved for future generations.

Individuals can also benefit from simply knowing that a species or habitat itself exists; this is known as existence values. People who have never seen or visited an area can also get enjoyment from the known presence of an MPA, as the mere existence of the area is valuable to them.

Lastly, option values arise from uncertainty about the future demand, or supply of, a good and service. MPAs elicit option values – they help ensure the option of having an ecosystem service in the future (like the provision of seafood or other harvestable resources), thus acting as an environment insurance policy in turbulent times.

Planning MPAs to maximize benefits to human well-being

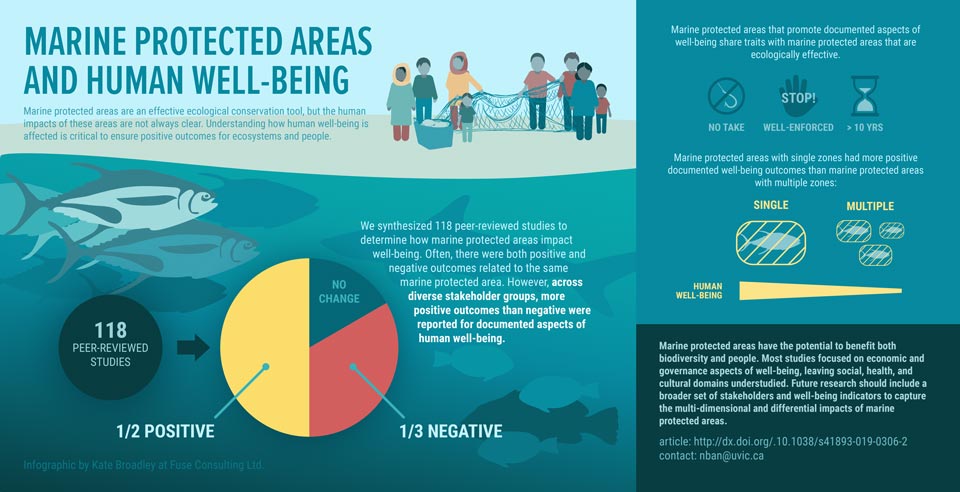

It is important to acknowledge that MPAs can have both positive and negative implications for resource users and communities. Yet a literature review of the MPA research shows that overall, MPAs have more positive than negative outcomes for human well-being across a wide range of groups who rely on the ocean.

The above review also found that there are specific characteristics of MPA design and management that can maximize the benefits to both biodiversity and human well-being. For MPAs to reach their full potential, research suggests that they should be:

- “no-take” MPAs – meaning no harvesting or resource extraction is permitted;

- well-enforced; and

- over 10 years old.

Other characteristics require trade-offs between biodiversity and human well-being, MPA size being one example. Large MPAs tend to better meet conservation objectives, but are often economically or institutionally impractical. On the other hand, small MPAs tend to deliver more positive well-being outcomes for local people, but may fail to address a myriad of ecological threats facing marine environments.

MPA networks – collections of small to medium-sized MPAs that work together to broaden ecological and social benefits of individual MPAs – offer a good compromise. This is the approach being taken in the Great Bear Sea off the central and north coast of BC, to develop Canada’s first MPA network.

Graphic provided with permission from Dr. Natalie Ban, University of Victoria

Canada’s first MPA network

Similar to other successful MPA networks in other parts of the world, the MPA network planning process in BC is being co-developed with First Nations and with careful consideration of multiple stakeholders and the diverse needs for conservation, resource management and sustainable development. In order to be ecologically effective, the network is being designed to incorporate multiple ecological principles (e.g., MPAs that are connected, adequate, representative and efficient) into its design parameters (e.g., size, shape, and spacing). At the same time, it is being planned to reflect the local context and accommodate the needs of multiple users and communities. Adequate stakeholder engagement is and will continue to be central to this process.

Once implemented, the MPA network in the Great Bear Sea will be a step forward in ensuring marine environments continue to provide benefits for people and communities for generations to come.

Top photo credit: Chris de Rham via Flickr Creative Commons

This is the 5th blog in a series about the benefits of marine protected areas.

Part 1: Climate change was front and centre this summer: let’s focus on ocean protection this fall

Part 2: Will big marine protection commitments at COP26 inspire Canada?

Part 3: Marine protected areas are an “insurance policy” in turbulent times

Part 4: Marine protected areas are central to our blue economy

Part 5: How protecting the ocean helps humans in return

Part 6: How better ocean management can promote food security