Many people who are concerned about climate change were excited when, in March 2025, Mark Carney became Prime Minister. As Governor of the Bank of England, Carney played a leadership role in international conversations about addressing climate change. Now, as Prime Minister of a country that has seen whole communities burn to the ground and evacuations from climate-fueled floods, surely he would act with the urgency that climate change demands.

Instead, the new Prime Minister has walked back key climate rules, making it impossible for us to meet our 2030 climate target and harder to meet our 2035 target. As the climate crisis worsens, Canada is falling further behind in its efforts to reduce its greenhouse gas pollution. This post attempts to summarize where Canadian climate action stands almost a year after the Prime Minister took office.

The big picture: Will Canada meet its current climate targets

Over the years, Canada has set a number of targets for reducing greenhouse gas pollution. It has missed every single one.

In 2021, Canada enacted the Canadian Net Zero Emissions Accountability Act (CNZEAA), which was supposed to break this pattern of broken promises, setting up structures that would require the government to set (hopefully ambitious) targets, make credible plans for meeting those targets, and publish regular reports on progress with course-corrections where needed.

Under CNZEAA, Canada’s current targets are to reduce its emissions (as compared to 2005 levels) by 40-45% by 2030, with an interim commitment of 20% reductions by 2026, with an ultimate goal of being “net zero” by 2050. The Act requires the government to prepare a plan outlining its efforts to achieve these targets and to report regularly on how it will do so, making corrections as needed.

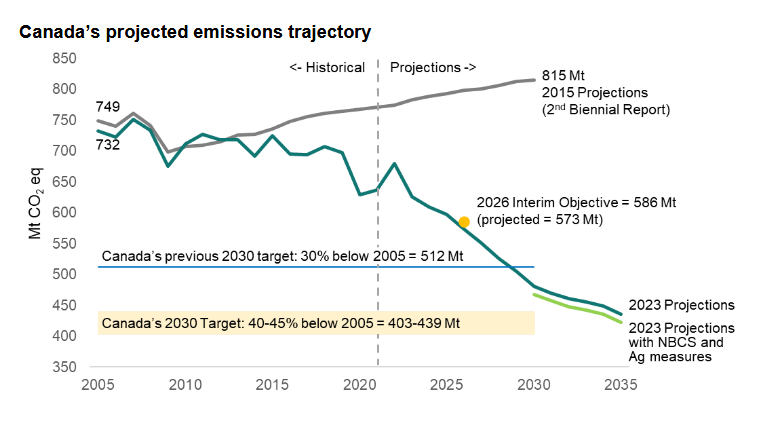

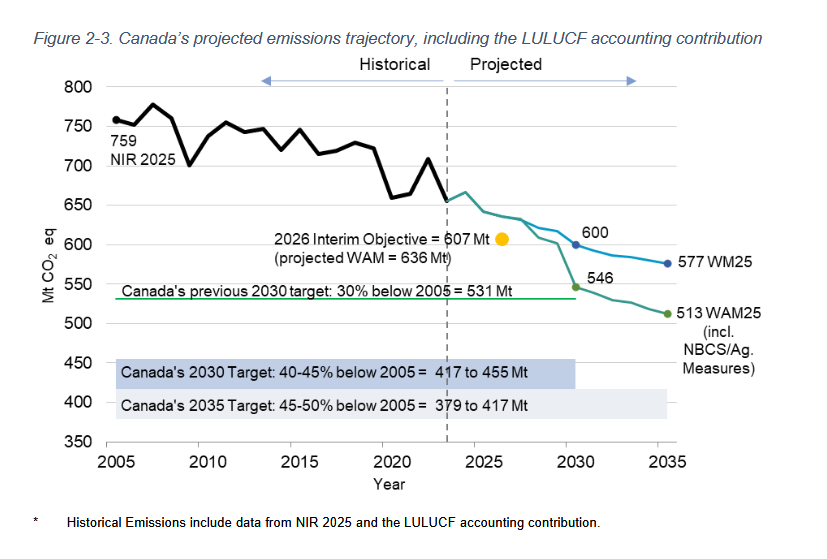

Canada’s 2023 progress report projected that the country was on track to achieve the 2026 target, but that without additional efforts, the 2030 target would not be achieved. The report also noted that Canada would beat a weaker 2030 target set by the Harper government in 2015 of reducing emissions by 30%.

But two years later – after a series of government decisions described later in this post – the 2025 progress report tells a different story. Quietly released in January 2026, the country is no longer on track to achieve either the 2026 target or the previous government’s weaker 2030 target. The country’s actual commitment of 40-45% reductions by 2030, and a new 2035 target, seem increasingly out of reach.

Not all the differences between the two reports’ projections are necessarily the result of changes in government policy. Many global economic and political factors are beyond the control of the government, and changes in modelling best practices could also play a role. Still, it is clear that recent policy changes have not helped.

So what’s the Carney government done on climate in its first year?

In the past year, Prime Minister Carney has repealed the consumer carbon tax and replaced rules around electric cars. While he has pledged a stronger industrial carbon price, funding for clean energy and laws regulating methane leaks from oil and gas operations, he also entered into an agreement with Alberta that would further weaken climate laws. Here are the details.

Carbon pricing

Economists argue that the most effective and cost-effective way to reduce pollution is to make sure people cannot pollute for free – known in environmental law as the polluter pays principle. Pollution harms us all, but often that harm is not reflected in prices, resulting in poor business decisions.

Canada’s climate plan includes two types of carbon pricing: a consumer carbon price paid by end-users of oil and gas, and an industrial carbon price paid by factories and businesses that produce greenhouse gases in the course of their business operations.

According to the 2023 progress report, Canada’s carbon price, a “fundamental measure” in the climate plan, was expected to result in “about a third of projected emissions reductions in 2030.” This statement does not differentiate between the consumer and industrial carbon pricing schemes.

By 2024, years of misinformation campaigns originating with political parties and the oil and gas industry had convinced many Canadians that the consumer carbon price was driving up inflation and the cost of living, despite the fact that most families received Climate Action Incentive rebates that more than covered the costs of the carbon price. Ironically, at least some of the increased costs being experienced by Canadians (such as grocery price hikes) were the result of climate change, rather than the carbon price.

In this political climate, one of Mark Carney’s first actions as Prime Minister was to set the consumer price to $0/tonne, effectively eliminating it. The consumer carbon tax was expected to reduce Canada’s annual emissions by 19-22 megatonnes per year by 2030 (about 8-9 percent of the expected emissions reductions). While the industrial carbon price remains in place (more on this below), the end of the consumer carbon tax introduces a significant gap in Canada’s plan to achieve its climate goals.

EV sales mandate suspended

Transportation is one of the major sources of greenhouse gas pollution – with carbon dioxide coming from every internal combustion engine on the road. The electric vehicle (EV) sales mandate was intended to ensure that EV cars are available for purchase in Canada by requiring auto manufacturers to sell a certain percentage of electric cars (20% in 2026). This regulation took years to develop, with a detailed strategic environmental assessment and public consultation. According to the government:

[t]he cumulative greenhouse gas emission reductions from 2026 to 2050 are estimated to be 430 millions tonnes, valued at $19.2 billion in avoided global damages.

Under pressure from the auto industry, Prime Minister Carney suspended this legal requirement on September 5th, 2025. On February 5th, as this post was being finalized, the government announced that it was shelving the EV Mandate and weakening Canada’s EV targets; instead the government will fund a further round of rebates to people who purchase EV vehicles.

Oil and gas industry vs climate action

Canadian climate policy has long attempted to reduce emissions without imposing too many restrictions on one of Canada’s most polluting industries: the oil and gas sector. Because the harm caused by oil and gas does not show up on industry balance sheets, Canada’s oil and gas industry appears to be profitable, and successive governments have relied upon it for tax revenue and job creation.

As a result, direct emissions from the sector have increased dramatically, rising to about a quarter of Canada’s emissions – without even counting the emissions from their products when they are eventually burned (which are still larger).

Recognition that the sector’s emissions played a major role in Canada’s ongoing failures to achieve its climate commitments caused the government to announce, in 2021, that it would be imposing a cap on Canada’s oil and gas emissions. According to the 2023 progress report, the cap was necessary to “ensure that the sector makes an ambitious and achievable contribution to meeting the country’s 2030 climate goals.”

The government planned to support the industry in meeting the cap through massive subsidies for carbon capture and storage (CCS), a technology that industry believes could allow it to reduce those direct emissions while increasing the amount of oil and gas produced (and therefore burned). CCS involves sucking carbon dioxide out of the stacks of industrial facilities and then storing it so that it does not enter the global atmosphere. Even if CCS could reduce the point-source emissions of oil and gas facilities (which is not a given), using it to justify increased production will only lead to significant increases in global emissions.

Regardless, in Budget 2025 the Carney government doubled down on oil and gas industry subsidies for CCS, while at the same time signaling that it was likely to abandon the oil and gas emissions cap, in favour of a strengthened industrial carbon price.

In addition, in a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) agreement with the Province of Alberta, the Prime Minister indicated an openness to allowing the construction of a massive new pipeline to BC’s north coast, and to suspending the Clean Electricity Regulations in the province.

Other announced changes

There are other climate policy changes, both positive and negative, under Carney.

Budget 2025 unveiled a Climate Competitiveness Strategy which promised more funding for clean energy.

The federal government has moved forward on Clean Energy Regulations, governing the emissions from electrical generation facilities in the country. However, the MoU signed with Alberta suggested that the government might accept a weakened form of the regulation in that province – a disturbing precedent which could undermine the effectiveness of the regulations nationally.

In more positive news, long-promised regulations to reduce the escape of the potent greenhouse gas methane from oil and gas operations have been unveiled.

Consultations on Industrial Carbon Pricing

The Carney government has not only maintained the industrial carbon price, but has signaled that industrial carbon pricing will be a primary tool to reduce emissions, one that justifies the relaxing of other climate policies. The government argues that the industrial carbon price is expected to have a more immediate effect on emissions than the consumer carbon price would have had.

Consequently, it is critical that the government’s revised industrial carbon price, the Output Based Pricing System (OBPS), is strong and enforced. One of the weaknesses of the current system is that the Governor in Council (federal Cabinet) has broad discretion to decide that the OBPS does not apply in a province that has its own pricing system, even if the provincial system is not as strong as the OBPS. West Coast is recommending that the law and regulations be strengthened so that Cabinet can only rely on provincial pricing systems that actually meet or exceed the standards (benchmark) of the federal system.

What do frequent course changes mean for climate action?

There are many ways to achieve a climate goal, and it is certainly open to a government to change its policies over time, especially as circumstances change.

However, changes in climate action raise the obvious question – is there a new plan and can it achieve Canada’s climate targets as well or better than the old plan? The Climate Plan unveiled in 2022 included many of the tools and policies that Prime Minister Carney has, with the stroke of a pen, eliminated or weakened.

Laws, regulations and policies usually do not have an immediate effect when they are enacted. It takes time for rules to be developed and enforced, and for industry and the public to act on the incentives that the rules create. New laws or rules may take even longer if a potential change in the political winds mean that industry can reasonably believe that actions promised in one year may be reversed in the next, meaning that early adopters may end up spending money for nothing.

The CNZEAA was intended to create a structure that ensured transparency and consistency in action on climate change. The fact that a government is required to create a climate plan, and report on its progress, is intended to keep governments accountable.

However, Prime Minister Carney apparently believes that he can eliminate key features of the plan without even having to explain what the impacts of his changes are on achieving the climate targets or how he will make up the resulting gap in meeting the target. If the plan can be modified on a political whim, without an explanation of how the climate target will be met, then the law is not actually working as intended.

Former Environment Minister, Stephen Guilbeault, resigned from Cabinet over Carney’s agreement with Alberta, apparently for this reason. As he noted:

“I think that my government needs to be honest with Canadians,” Guilbeault said in an interview with CTV Power Play with Vassy Kapelos on Wednesday. “With the rollbacks that we’ve seen over the past few months on different climate change measures that have been adopted over the years by me and some my predecessors, it is impossible to see how we achieve our 2030 targets. … The math doesn’t add up.”

In particular, Guilbeault noted that suspending the Clean Energy Regulations would mean that Canada would need to increase its industrial price on carbon to $400/tonne (far higher than is proposed) to make up the difference.

CNZEAA was never as strong as West Coast Environmental Law and our allies wanted, but the lack of any effort to deliver on the intent of the law demonstrates just how weak it is.

Conclusion

Unfortunately, Canada’s progress towards its climate targets is stalling. But those figures raise as many questions as they answer, and demonstrate the need for more transparency and more ambition from the federal government, along with stronger laws to help ensure that ambition exists.

First, Canada should clearly explain why our progress has slipped. Is it, as appears to be the case, because of political choices by the government to repeal or delay climate action that they had previously committed to? If so, to what extent? This transparency needs to be ongoing – with any future short-comings immediately explained and addressed so that we do not lose momentum to our climate targets.

Second, what is Canada’s plan to meet our legislated climate targets – and break from our track record of promising big and then failing to do what is required to meet those commitments? So far, a lot of emphasis appears to be on the OBPS, but Canada’s climate plan has long had a price on industrial pollution—and it was always meant to function as one strategy among many. The government needs to clearly tell us how it will make up for the shortfalls that weakened climate action and other circumstances have created.

It is true that the nation’s attention has been captured by economic and geopolitical threats and the cost of living. However, it is at these times that we need politicians with long vision that can plot a course that achieves our short- and long-term needs, without sacrificing the economy of tomorrow for short-term political points. And if they choose to prioritize short-term economic security over long-term economic and climate security, they need to be honest about that choice – rather than asserting, without evidence, that we can still make our climate targets with weakened climate laws and policies.