For almost twenty years Taseko Mines Ltd. has claimed it is impossible to develop its Prosperity gold and copper mine without destroying Fish Lake (known to the Tsilhqot’in people as Teztan Biny). Prosperity received a “scathing” report from the federal review panel charged with investigating the proposal, due in part to concerns about the lake’s destruction. The federal government refused to issue the project an Environmental Assessment Certificate, and just two days later, on November 4th, 2010, Taseko announced that it would be submitting a revised mining plan that spared Teztan Biny.

For almost twenty years Taseko Mines Ltd. has claimed it is impossible to develop its Prosperity gold and copper mine without destroying Fish Lake (known to the Tsilhqot’in people as Teztan Biny). Prosperity received a “scathing” report from the federal review panel charged with investigating the proposal, due in part to concerns about the lake’s destruction. The federal government refused to issue the project an Environmental Assessment Certificate, and just two days later, on November 4th, 2010, Taseko announced that it would be submitting a revised mining plan that spared Teztan Biny.

The revised plan was first submitted to the government in February 2011, raising questions (as West Coast reported at the time) about how the company could come up with a solution that had not been considered in the original assessment. The Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency (Agency) needed additional information from Taseko, so the plan was not made public at the time.

On August 9th, 2011 the Agency announced that it had received a complete revised project description for what is now called “New Prosperity”. The Agency has 90 days to decide (no later than November 7th) whether or not that project should undergo an environmental assessment (EA) or be rejected at this stage.

Now that the project description is publicly available, we can say: West Coast does not believe that the New Prosperity proposal is substantially different from the options already reviewed and rejected by the federal review panel. EA laws should not allow a proponent to submit what is essentially the same project multiple times. To do so would be costly to tax-payers, create uncertainty for the public, First Nations and investors alike, and provide inadequate environmental protection.

Is New Prosperity a different project than the original Prosperity?

In the Environmental Impact Statement for the original Prosperity (March 2009, Vol.2), Taseko concludes there were three technically feasible mine development plans, of which “Option 3 provides the lowest environmental risk and is the only economically viable option” (page 6-85). Pages 6-55 to 6-56 go into more detail, concluding that:

- “there is a higher significance of failure associated with Options 1 and 2 relative to Option 3 to water quality, fisheries and wildlife/biophysical categories”,

- “there is greater risk associated with the tailings storage facilities, waste rock storage areas, and tailings and water management in Options 1 and 2 relative to Option 3; particularly with respect to water quality, fisheries, and wildlife/biophysical categories”, and

- “Option 3 is clearly demonstrated to be the lowest risk and most environmentally secure alternative”

It is important to note that the panel considered and rejected not only Option 3, but also Options 1 and 2: “the Panel agrees with the observations made by Taseko and Environment Canada that Mine Development Plans 1 and 2 would result ingreater long term environmental risk than [Option 3]” (page 50).

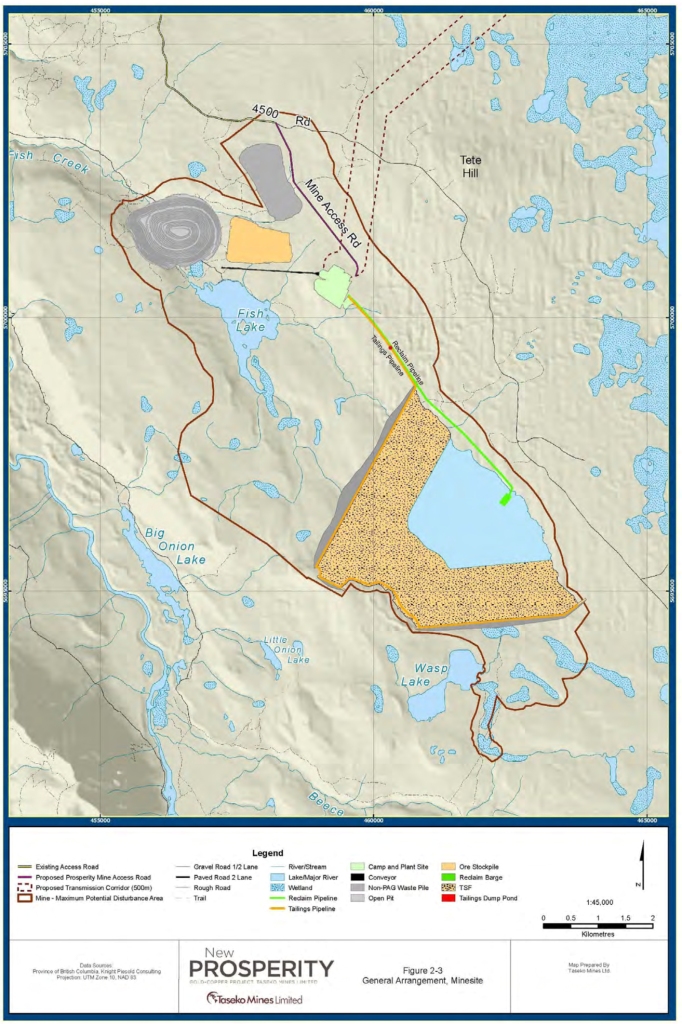

Taseko’sNew Prosperity project description (page 20) states that Prosperity

Option 2 is the basis for the New Prosperity design …The concepts that lead to the configuration of MDP Option 2 have been utilized to develop the project description currently being proposed.

Option 2’s economic disadvantage was described in the original panel report:

According to Taseko’s economic analysis…the undiscounted life of mine capital and operating costs associated with this mine development plan would beapproximately $337 million more than the preferred option primarily due to the additional distance to transport waste materials as well as additional measures to mitigate seepage. [emphasis added]

It appears Taseko has essentially re-packaged Option 2 into a “New” Prosperity, claiming that changes in markets will allow it to afford the additional $300 million required to “save” Teztan Biny. As explained below, “New Prosperity” appears to propose only a delay in contamination, and if expansion for ‘full exploitation of the ore’ is undertaken, then also an eradication of Teztan Biny.

The New Prosperity proposal does not even make changes that the panel recommended. For example, Taseko emphasizes that there are “no design changes in the New Prosperity project compared to the proposal reviewed in 2009/2010 for the transmission line, existing rail load-out facility or road access.” However, the panel’s very first recommendation (of 24) was that the company re-examine the transmission line corridor.

Would Option 2 save Teztan Biny?

Taseko suggests that Option 2 was rejected solely for economic reasons and now due to rising gold and copper prices it is “no longer flawed as a result of excessive economic risk” (project description page 20). However, Option 2 was also rejected for a host of environmental reasons. The panel agreed with Taseko (statement at page 37) that Option 2, with its tailings storage facility located upstream of Teztan Biny, would avoid short term destruction, but in time likely result in contamination of Teztan Biny (page 50).

Taseko suggests that Option 2 was rejected solely for economic reasons and now due to rising gold and copper prices it is “no longer flawed as a result of excessive economic risk” (project description page 20). However, Option 2 was also rejected for a host of environmental reasons. The panel agreed with Taseko (statement at page 37) that Option 2, with its tailings storage facility located upstream of Teztan Biny, would avoid short term destruction, but in time likely result in contamination of Teztan Biny (page 50).

The possibility of ‘saving’ Teztan Biny was thoroughly examined by the review panel. Government agencies even requested a fourth option be reviewed to explore all avenues of mitigating effects on the lake (page 43 of panel’s report).No matter how it is configured, Teztan Biny cannot remain a healthy ecosystem in the presence of the mine, and in particular if any mine expansion is carried out, the lake will inevitably be subsumed due to the location of the ore body. Taseko’s VP Engineering Scott Jones submitted to the review panel that:

You might be able to delay [deterioration of water quality] by moving the tailings facility farther away to Fish Creek south. You may even be able to minimize that, reduce it by mitigation measures that could be applied. But eventually that water quality will change. [emphasis added]

Taseko, Environment Canada and the panel all agreed that Option 2 would probably not prevent the destruction of Teztan Biny, only delay it. We are not aware of anything in Taseko’s re-packaged Option 2, New Prosperity, that changes that.

In addition to the impact on Teztan Biny, New Prosperity still eliminates Y’anah Biny (Little Fish Lake) and the Nabas region generally (page 105). Even if we are fortunate and it does not contaminate Teztan Biny, it will make the lake inaccessible and surrounded by significant industrial activity. New Prosperity will still have significant adverse impacts on Tsilhqot’in current use, cultural heritage and Aboriginal rights. New Prosperity will still destroy up to 81% of present spawning habitat, and the idea of compensation habitat has been weakened (page 105). New Prosperity does not address the factors required by the federal government in its rejection of the original project. We believe New Prosperity, or at least all the components thereof, is an option that has already been reviewed and outright rejected by the review panel.

How should the Agency deal with New Prosperity?

Taseko has, until this juncture, been consistent in its assertion that this project cannot be successfully undertaken while maintaining the ecological function of Teztan Biny. Section 16(2)(b) of the Canadian Environmental Assessment Actrequires a proponent to present not only its preferred plan, but also all feasible alternatives and the environmental effects thereof.

Taseko is now requesting that the federal government review its “New” Prosperity project and have the public, First Nations, and other government departments who just finished devoting time, resources and energy to participating in the EA process undergo another EA for essentially the same project.

The law has always rejected the idea of giving parties the opportunity to argue the same case over and over again. In various contexts the courts have referred to the idea that a final decision should be final using the Latin phrases res judicata (a matter already judged), functus officio (having performed its function), and by ruling that initiating multiple actions on the same matter is an abuse of process. The reasons are clear: parties should not be allowed to endlessly try an issue before the courts or a tribunal in the hopes of achieving a particular or preferred result.

As the Supreme Court of Canada stated:

[T]he underlying rationale for the [functus officio] doctrine is clearly …that for the due and proper administration of justice, there must be finality to a proceeding to ensure procedural fairness and the integrity of the judicial system.

The Supreme Court has emphasized that for many tribunals the doctrine of functus officio should be applied flexibly, and not in a formalistic way. We do think that if Taseko were to come back with a fundamentally different design that addressed the panel’s concerns and that had reduced environmental impacts, that a new EA would be appropriate. In a case such as this, however, where the new proposal includes only minimal changes from an option that was already fully considered, we believe that the doctrine should apply with full force.

Regardless of whether the legal principle applies directly, the underlying policy rationales of efficiency, reduction of duplication, finality and certainty apply, especially in light of substantial funding cuts for the Agency and other federal departments. It is an abuse of process for Taseko to seek another EA, arguing the opposite of their position before the review panel in the original hearing – that Teztan Biny can be “preserved” from contamination and that this option has lesser environmental impacts.

If Taseko’s “New” Prosperity is permitted to undergo another EA, a very poor precedent will be set. Such a decision would:

- encourage poor corporate behaviour in the conduct of EAs where proponents would be encouraged to submit the lowest cost/highest profit proposal, knowing they could re-apply with less profitable alternatives in the rare event that the proposal is rejected;

- set a poor policy direction, where this unique circumstance would proceed without reference to considered policy or legislation to guide the participants, the Agency, the Responsible Authorities or the panel. This may be in part the fault of the federal government, which ‘invited’ Taseko to address the deficiencies listed in the original report but did not set out guidelines on how a resubmission following a rejection would be handled; and

- show disrespect to the EA process itself, the thorough review that the members of the panel conducted for Prosperity, and the members of the public, organizations and First Nations who diligently participated in the federal and provincial processes to date.

In addition, we would argue that the ability to enter into environmentalcommitments in a project the scale of New Prosperity, which is projected to be in operation for at least 20 years, should not be predicated on the basis of market prices for gold or copper. Taseko has said that because gold and copper prices are now higher, they have ‘extra’ profit to put toward the alleged preservation of the lake. While these prices are trending higher now than during the assessment of Prosperity, just last week gold was “dragging down” stock markets, copper prices were sliding in part due to lack of demand, and generally prices for such commodities are volatile in the current economic climate. In addition, if commodity prices rise, the more profitable it will be to expand the mine and maximize recovery of the ore deposit, which will necessarily mean directly impacting or taking over Teztan Biny.

The review panel for Prosperity thoroughly reviewed Option 2, and any other components making up New Prosperity. That should be the end of the matter.

Where do we look for guidance?

The Agency has no policies dealing with this type of situation. Only two other projects have ever been rejected outright, by a federal review panel: Kemess North and Whites Point Quarry and Marine Terminal. In those cases, however, the proponent has not come back seeking approval of essentially the same project and thus, to our knowledge, there is no precedent, no statutory provision, and no policy to help the Agency navigate this process or to provide the public, First Nations or the proponent with a sense of how to proceed. Section 24 of the CEA Act does stipulate appropriate information from previous EAs must be used, but the intent of this section is to apply to modifications or expansions of existing, approved projects.

Meanwhile, under the constant watch of investors, Taseko is operating as though “New” Prosperity will get the go ahead. Taseko states that an EA “will begin on or before November 7, 2011” and that they ‘expect’ a comprehensive study, neither of which are for Taseko to determine. The company’s 2010 Annual Report (page 5) confidently states “management has been assured that the Government of Canada is not opposed to mining the ore body.” Taseko is also hiring for a Manager of Environmental Permitting for New Prosperity.

This type of posturing is only possible because the federal government has not made it clear when or how a rejected project may resubmit, if at all, and how a revised project will be conducted.

In our view the Agency and the Responsible Authorities should exercise their discretion and terminate any need for another EA of this project (sections 5 and 26 of the CEA Act). If an EA were to proceed, many important questions remain, including:

- when would the project be referred to a review panel (which we believe is the proper track), and who would be on the panel,

· to what extent would the findings in the panel’s original report bind subsequent decisions about the project,

- what legitimate expectations and procedural rights do affected parties have,

- how would the “new” project be scoped,

- how can the Crown meet its duty to consult and accommodate First Nations, again,

- what is the status of the review panel’s existing 24 recommendations,

- how should the public be involved,

- how is the province’s Environmental Assessment Certificate #M09-02 affected,

- and many more…

These are not the type of decisions that should be made on an ad hoc basis, on poor facts or in relation to a project that should not even be in the EA process. Thus, accompanying the refusal decision on November 7, 2011 should be a set of legal and policy reasons why the Agency and the Responsible Authorities refuse to conduct another EA, including the legal and policy reasons we cite above. This set of reasons will form the basis for legislative reform and policy development to address any such subsequent attempt by a proponent in the future to abuse the environmental assessment process.

By Rachel Forbes, Staff Lawyer with research from Anna Novacek, Legal Intern