Bio-waste spread on farmland threatens to contaminate local wells. Pesticide spraying by a logging company is destroying bird habitat. Odours and rodents from a composting facility disturb a rural neighbourhood. Logging on steep slopes threatens a community’s drinking water. A developer is given the go-ahead to build on a floodplain that provides habitat for salmon.

What do these scenarios have in common? (Other than the fact that they are real-life issues that we have helped British Columbians with in recent years.)

In each of these situations, private professionals (engineers, biologists, foresters, etc.), rather than government staff, get to determine what level of public risk and inconvenience is appropriate. Professionals hired by industry sign off on the plans, and in many cases the government may not ever review a plan or check to see if the law has been followed.

Over the last 15 years, BC’s environmental and public health laws have increasingly turned over these decisions to industry in the name of “professional reliance,” but we think the more appropriate term is “regulatory outsourcing.” In each of these cases the government has eliminated or limited its decision-making powers over what happens to public rights, public lands and public resources.

In theory, these professionals are supposed to be following rules set by the government and/or their professional associations. In practice, however, vague terms, poorly written rules and virtually non-existent enforcement mean that consultants hired by developers are making decisions with huge implications for our environment and public health.

Clearly professionals (including lawyers) – whether they work for government, industry or the non-profit sector – have a lot of training and expertise, and we would be well-advised to take their analysis and recommendations seriously. At the same time, we need to recognize the appropriate roles of government and private professionals and ensure that we do not lose public accountability and transparency through inappropriate reliance on professionals, including through regulatory outsourcing.

The government needs to hear from you

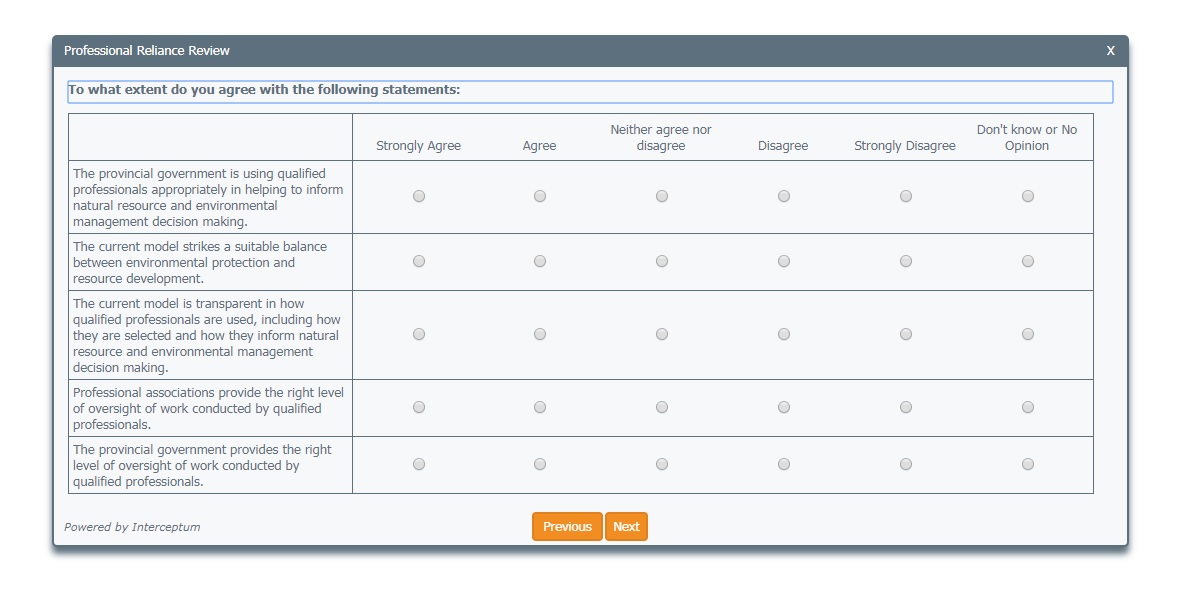

The BC government is currently undertaking a public consultation on professional reliance, and needs to hear from as many British Columbians as possible before January 19th, 2018. The government especially needs to hear firsthand examples from communities and individuals that have experiences with private professionals working under BC’s laws, but everyone should express their concern and call for stronger environmental laws.

To participate, you can fill out a short survey. Or, if you have more to say, I strongly encourage you to write a letter and email it to citizenengagement@gov.bc.ca.

Looking for ideas on what to say in your submissions to government?

Together with a coalition of other non-governmental organizations that are concerned about regulatory outsourcing, we have developed the following principles which we believe should guide the use of professionals under BC’s environmental statutes.

We must:

- Stop degrading the health of BC’s ecosystems, and restore the environment where degraded.

- Guarantee that an unbiased decision-maker hears from an informed public on decisions that affect their health or environment.

- Ensure that First Nations are engaged and their rights respected.

- Ensure that BC’s laws are clear, enforceable and enforced.

- Use “professional reliance” only where appropriate and in ways that protect the environment and health.

- Set standards that require professionals to be professional.

1. We must stop degrading the health of BC’s ecosystems, and restore the environment where degraded.

Laws must make it clear that the purpose of all decisions under resource, public health and environmental statutes is to promote sustainability and public health. Professionals, whether working for the government or for industry, must have an ethical and legal obligation to pursue those objectives. Projects must make a net contribution to sustainability and address cumulative impacts, including our contribution to climate change.

2. We must guarantee that an unbiased decision-maker hears from an informed public on decisions that affect their health or environment.

One of the oldest and best protected legal rights is the right of a person who will be affected by a government decision to be heard by an unbiased decision-maker. Where a government decision relates to a threat to human health, the right to an unbiased decision-maker takes on a constitutional dimension.

Professionals hired by industry are not unbiased decision-makers. No matter how professional they may be, the fact that they receive a payment from an interested party creates an apparent conflict of interest and undermines public confidence in the decision.

For this reason, decisions that relate to projects that pose a significant risk to human health or the environment must be made by government, and not outsourced to industry professionals.

In addition, to allow the public to participate fully in decisions, there must be easy access to information about environmental and health decisions, including access to reports prepared by industry-hired professionals.

Where decisions threaten human health or the environment, members of the public must have a broad right of appeal.

3. We must ensure that First Nations are engaged and their rights respected.

First Nations have constitutionally-protected Title and Rights, as well as a right to be consulted and accommodated on decisions that affect their rights. It is the government’s job to ensure that these rights are protected – and consultation with Indigenous governments must take place on a government-to-government basis, taking into account traditional knowledge, and in a manner consistent with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Government cannot adequately meet its constitutional and international obligations if it has outsourced its decision-making to private parties. Consultation, and the decisions based on it, must remain primarily the responsibility of government.

4. We must ensure that BC’s laws are clear, enforceable and enforced.

BC’s forestry laws require private professionals to judge whether protecting water or wildlife will “unduly restrict the supply of timber.” But what does “unduly” really mean? It’s a vague and unenforceable term that requires professionals to make arbitrary choices about the balance to be struck between the interests of their employers and the rights of the public. This is unacceptable.

Laws that protect human health and the natural environment must set clear, verifiable and measurable standards and create clear consequences for non-compliance.

At the same time, the government has failed to enforce environmental and public health laws. Lax enforcement means that companies and consultants that break the law are not caught, while those who follow the law are at a competitive disadvantage.

The government must ensure that its enforcement agencies have the resources, training and culture they need to detect and prosecute law-breakers. Laws and policies must encourage and protect whistleblowers and citizens who call for enforcement against law breakers.

5. We must use “professional reliance” only where appropriate and in ways that protect the environment and health.

Professionals do have a role in making decisions that protect the environment and promote public health – but in all cases the government must keep the power and responsibility to act as a “responsible owner” of public land and resources, and to ensure that decisions that could harm the public and First Nations are made by unbiased decision-makers.

In addition, a “Sustainability Board” must be created with the power to investigate and monitor government and professional actions that could negatively harm human health and the environment, and to make recommendations for better practices. While drawing on existing tribunals, the Board must have broad powers to review and overturn unsustainable or unhealthy decisions made by professionals or government, and to issue sanctions and penalties, including against professionals.

6. We must set standards that require professionals to be professional.

The best professional in the world is still human – still influenced by their employer, by their desire to appear competent, and still fallible. We need structures that:

- encourage professionals to protect public health and the environment,

- ensure that unprofessional decisions giving rise to such harm are detected and remedied; and

- hold professionals accountable when they fail to live up to their obligations to the public.

Government must require proponents seeking government approval to use professionals from a roster of qualified individuals that have demonstrated specific qualifications in relation to statutory functions. Individuals who fail to protect human health and the environment or to maintain a standard of professionalism should be removed from this roster.

Government must also enact laws that:

- clarify the responsibility of professional associations in relation to public functions,

- clarify the circumstances in which professionals will be held liable for their decisions;

- require that professionals hold insurance related to circumstances in which they may be liable,

- compel professionals to report work that falls below professional standards; and

- ensure that there is periodic auditing and review of work done by professionals.

Take action now

Our submissions to the professional reliance review will be based on the need to avoid regulatory outsourcing and these six principles.

We hope that you too will take the time to let the government know what you think (either through their survey and/or by emailing your written submission). Input must be submitted by January 19th, 2018.

Click here to fill out the BC government's online survey.

What we tell the government during this process can help determine how public health and the environment is managed in BC for years to come.