On April 11, 2014, the Yinka Dene Alliance (“YDA”) held an All Clans Gathering in Nak’azdli (adjacent to Fort St. James) in order for their leaders and elders to issue reasons for the rejection of the Enbridge Northern Gateway pipeline in a gathering according to their laws. I was grateful to be invited as a witness at the gathering along with West Coast’s executive director and senior counsel Jessica Clogg. The power of the gathering really underlined why the federal government’s decision to essentially ignore First Nations’ assertions of their laws and governance in relation to the Enbridge pipeline is a serious risk, not just from a relationship-building standpoint but also in the context of Canadian law.

The YDA is a coalition of six First Nations whose ancestral territories comprise approximately 25 percent of Enbridge’s proposed pipeline route. Since the early days of Enbridge’s proposal, First Nations of the YDA (which are also members of the Carrier Sekani Tribal Council) have been clear that they would evaluate the Enbridge pipeline pursuant to their own legal order. First Nations of the YDA have relied upon their laws and governance authority in both a procedural sense, by conducting their own studies of the Enbridge pipeline and calling for a parallel First Nations-led review of the Enbridge pipeline, and subsequently in a substantive sense through a determination to refuse consent for the Enbridge pipeline to pass through their territorial lands and waters, as expressed in the Save the Fraser Declaration.

The YDA is a coalition of six First Nations whose ancestral territories comprise approximately 25 percent of Enbridge’s proposed pipeline route. Since the early days of Enbridge’s proposal, First Nations of the YDA (which are also members of the Carrier Sekani Tribal Council) have been clear that they would evaluate the Enbridge pipeline pursuant to their own legal order. First Nations of the YDA have relied upon their laws and governance authority in both a procedural sense, by conducting their own studies of the Enbridge pipeline and calling for a parallel First Nations-led review of the Enbridge pipeline, and subsequently in a substantive sense through a determination to refuse consent for the Enbridge pipeline to pass through their territorial lands and waters, as expressed in the Save the Fraser Declaration.

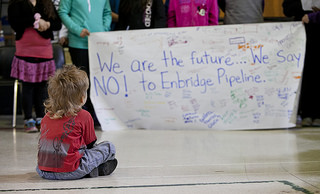

On April 11, Yinka Dene people filled the Chief Kwah Memorial Hall in Nak’azdli for the All Clans Gathering, many of them travelling hundreds of kilometres. Seating at the gathering was arranged into four quadrants, each representing one of the four clans of the Yinka Dene, and attendees sat with their fellow clan members. As witnesses, Jessica and I were asked to sit with the Beaver Clan. Nak’azdli First Nation’s elected Chief Fred Sam, who offered a welcoming following the singing in of the hereditary leaders, stated that:

This gathering is about our people giving the reasons for our rejection of the Enbridge pipeline, in our voices, on our lands, under our laws.

A delegation of six federal officials responsible for First Nations consultation on the Enbridge pipeline attended the gathering to hear the reasons for decision.

The significance of the gathering was summarized by Hereditary Chief Tsodih, Nak’azdli, as follows:

It’s important for the Canadian government, and the public in BC and Canada, to know that our people act according to principles and responsibilities in our own system of law and governance. This gathering of our clans, for our leaders and elders to give reasons for the rejection of the Enbridge pipeline in an assembly according to our laws, affirms that our ban on the Enbridge pipeline isn’t a preference, it’s a determination under law.

Both video footage and images from the gathering are publically available.

What does the rejection of the Enbridge pipeline pursuant to Yinka Dene law mean in the Canadian legal system? To address that question it is first necessary to look at how Canadian courts have considered Indigenous law generally. As a starting point, it is clear that Canadian common law recognizes the existence and exercise of Indigenous laws. In the words of Canada’s current Supreme Court Chief Justice Beverly McLachlin in R. v. Van der Peet (in dissent, but on another point):

The history of the interface of Europeans and the common law with aboriginal peoples is a long one. As might be expected of such a long history, the principles by which the interface has been governed have not always been consistently applied. Yet running through this history, from its earliest beginnings to the present time is a golden thread the recognition by the common law of the ancestral laws and customs the aboriginal peoples who occupied the land prior to European settlement.

There are different possible ways that an exercise of Indigenous law can be recognized in Canadian law. An exercise of Indigenous law may be connected to Aboriginal title, which in the words of the Supreme Court of Canada in Delgamuukw v. British Columbia includes “the right to exclusive use and occupation of land” by First Nations and “the right to choose to what uses land can be put.” The Supreme Court of Canada noted in Delgamuukw that

... the source of aboriginal title appears to be grounded both in the common law and in the aboriginal perspective on land; the latter includes, but is not limited to, their systems of law.

In discussing Aboriginal title in R. v. Marshall; R. v. Bernard the Supreme Court quoted with approval the statement of Indigenous legal scholar John Borrows that:

Aboriginal law should not just be received as evidence that Aboriginal peoples did something in the past on a piece of land. It is more than evidence: it is actually law.

The exercise of Indigenous law may also be linked with other constitutionally-protected rights of a First Nation, particularly governance rights. The current law laid out by the Supreme Court of Canada in R. v. Pamajewon is that Canadian courts will consider Aboriginal governance rights on a subject-by-subject basis depending on the particular facts at issue, using the same test that a Court applies to the determination of Aboriginal harvesting rights such as fishing or hunting. However, it is clear Canadian common law recognizes that Aboriginal peoples continue to act according to their own laws, and that those laws emanate from a constitutionally-protected governance authority which is distinct from the authority of the federal and provincial governments. The British Columbia Supreme Court found in Campbell v. British Columbia (Attorney General) that:

…aboriginal rights, and in particular a right to self-government akin to a legislative power to make laws, survived as one of the unwritten “underlying values” of the Constitution outside of the powers distributed to Parliament and the legislatures in 1867.

In making its ruling, the Court in Campbell noted that Aboriginal peoples had legal systems prior to the arrival of Europeans that continued after contact.

In making its ruling, the Court in Campbell noted that Aboriginal peoples had legal systems prior to the arrival of Europeans that continued after contact.

The United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, James Anaya, recently affirmed that Aboriginal governance rights are protected by Canada’s Constitution in his May 2014 advance report on the situation of indigenous peoples in Canada:

Notably, Canada recognizes that the inherent right of self-government is an existing aboriginal right under the Constitution, which includes the right of indigenous peoples to govern themselves in matters that are internal to their communities or integral to their unique cultures, identities, traditions, languages and institutions, and with respect to their special relationship to their land and their resources.

It is therefore clear that Aboriginal peoples’ exercise of their own laws can be recognized in Canadian common law, and their inherent governance authority afforded constitutional protection. What does this mean in the context of the Yinka Dene Alliance’s application of its own laws and its refusal of consent for the Enbridge pipeline?

As a starting point, the Supreme Court of Canada held in Haida Nation v. British Columbia (Minister of Forests) and subsequent decisions that, even in the absence of a treaty or court determination, land and resource use decisions that may affect First Nations’ asserted title and rights – which include governance rights and the decision-making aspects of Aboriginal title – require appropriate consultation with First Nations and, where appropriate, accommodation of the asserted title and rights. A decision made by Canada without appropriate consultation and/or accommodation may be set aside if challenged in court.

The federal government, for its part, has refused to support any First Nation-led review of the Enbridge pipeline and to date has not acknowledged or addressed the expressions of Indigenous law in relation to the pipeline. Instead, the federal government unilaterally proceeded with a review panel process carried out by the National Energy Board that has been roundly criticized by First Nations including the Yinka Dene Alliance as failing to address or incorporate Aboriginal rights, title, laws and values in the decision-making process. Several First Nations legal challenges of the Enbridge joint review panel recommendations are already underway.

The report of the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples also criticizes the federal government’s review process, stating that First Nations are required to deliver their concerns: “…to a federally appointed review panel that may have little understanding of aboriginal rights jurisprudence or concepts and that reportedly operates under a very formal, adversarial process with little opportunity for real dialogue.” The UN Special Rapporteur goes on to assert that: “Canada should endeavor to put in place a policy framework for implementing the duty to consult that allows for indigenous peoples’ genuine input and involvement at the earliest stages of project development.”

In this context, the federal government’s approach of largely ignoring First Nations’ assertions of the applicability of their laws to the Enbridge pipeline exposes the federal cabinet’s pending decision on the pipeline to legal challenge on the ground that Canada did not meaningfully consult and accommodate First Nations with regard to those issues.

Moreover, the Yinka Dene Alliance’s ruling upholding its ban on the Enbridge pipeline brings squarely into focus the more profound question of how the exercise of Aboriginal governance can and should interface with the exercise of federal or provincial law: a question that the Supreme Court of Canada in Mitchell v. M.N.R. has explicitly left open to be resolved. Many legal scholars have considered this issue in some detail, but in a general sense it is highly likely that the approach of the Canadian common law to this question will focus on reconciling the respective legal traditions of Aboriginal peoples and Canada. Given the circumstances described above, it will be difficult for the Canadian government to argue that its approach to decision-making on the Enbridge pipeline reconciles the Canadian law approach with the exercise of Indigenous law and governance.

If the federal government follows the joint review panel’s December 2013 recommendation to approve the Enbridge pipeline, there will be two conflicting conclusions reached through two different legal orders operating independently from each other: the Canadian government’s approval on the one hand, and on the other hand the refusal of consent by the Yinka Dene Alliance and other First Nations. Whether the focus of the resulting disputes is the duty to consult and accommodate, the application of Indigenous laws linked to Aboriginal title or governance rights, or other issues, such a situation will almost certainly result in further legal challenges, conflict and uncertainty for Enbridge’s beleaguered proposal.

In these respects, Canada’s unilateral approach to decision-making on the Enbridge pipeline creates significant legal and financial risk for the proposed project – a fact reflected in Enbridge’s inability to secure the required commercial support for the project from shippers who would use the pipeline.

By Gavin Smith, Staff Counsel