On April 24, 2025, United States President Donald Trump shocked the international ocean community by issuing an Executive Order promoting deep seabed mining on the US Continental Shelf and the international seabed. The Order was issued following lobbying by The Metals Company, a Vancouver-based company with a subsidiary in the US, as well as in the Pacific Islands states of Tonga and Nauru. The Metals Company’s US subsidiary has subsequently applied for permits to mine an area of the seabed between Mexico and Hawaii under the US Deep Seabed Hard Mineral Resources Act.

If granted, these permits would undermine international governance of the seabed under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), a foundational ocean treaty which has been ratified by 170 parties, including Canada. If the United States unilaterally issues permits to The Metals Company, this would open up the international seabed to a potentially dangerous activity, whose impacts are little understood, and it could create a precedent for greater conflicts in the high seas, and a race to the bottom.

In this blog post, we explain what’s at stake.

What are the potential environmental impacts of deep seabed mining?

Image: Mining-generated sediment plumes and noise have a variety of possible effects on pelagic taxa. (Organisms and

plume impacts are not to scale.) / Amanda Dillon (graphic artist)

The deep seabed covers roughly two-thirds of Earth’s surface, but because of its remoteness, we understand relatively little about it and the impacts that mining could have. Recent research suggests that it is an area of stunning natural diversity – experts estimate that over 80% of the marine animals discovered in the deep sea are “new to science.” We are also discovering the interconnection between life at the surface and in the depths. For example, we now know that nutrients from the deep ocean are carried to surface waters and feed phytoplankton, a species which is the foundation of most ocean food chains and which absorbs more than one-third of global carbon emissions annually.

Deep-sea species have evolved to survive in cold environments with little light or food by moving slowly, living longer and taking many years to reproduce. As a result, these species may be slower to recover if damaged. A 2019 study found that deep seabed areas subjected to a simulated mining experiment in 1989 had not yet recovered 26 years later. Tracks left by mining ploughs were still visible in the seafloor, and the areas had significantly less diversity of marine life than non-disturbed areas.

The mining that The Metals Company wants to undertake – the harvesting of polymetallic nodules on the seafloor – would involve scraping or disturbing the top layers of sediment from the seafloor, which sequester carbon and are home to deep sea life including sponges, corals, anemones and invertebrates. Among other impacts, seabed mining could also disturb the water column through the discharge of sediment plumes that could harm important global food sources like tuna fisheries.

Given these potential impacts and the scientific uncertainty, more than 900 science and policy experts from over 70 countries have signed a statement calling for a precautionary pause to deep-sea mining until the impacts to deep-sea ecosystems are better understood.

What is Canada’s position on seabed mining?

Since 2023, Canada has publicly supported a moratorium on commercial mining in the international seabed, given the absence of a comprehensive understanding of the environmental impacts and of a robust regulatory regime. With this statement, Canada joined 32 other countries calling for either a moratorium, precautionary pause, or ban on deep-sea mining in international waters.

Within national waters, Canada has stated that, in the absence of adequate scientific knowledge and a rigorous regulatory framework, it “will not authorize seabed mining in areas under its jurisdiction.” This position is effectively a moratorium on seabed mining in Canadian waters, although so far the moratorium has not been implemented in law.

How is deep-sea mining regulated under international law?

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) (1982), together with the 1994 Agreement relating to the Implementation of Part XI of UNCLOS (the 1994 Implementation Agreement), sets out the legal framework for governance of the international seabed and establishes an International Seabed Authority (ISA) responsible for developing regulations to govern international seabed mining.

Under UNCLOS, the international seabed and its resources are considered “the common heritage of mankind.” The ISA has established a regulatory system to govern mining exploration activities and has thus far awarded 31 exploratory contracts. The ISA has been developing regulations to govern mineral exploitation, or mining, which are currently in draft form. In the absence of a regulatory framework, the ISA has not considered any applications for mining, and as mentioned above, many are calling for the ISA to impose a moratorium on seabed mining.

In order to achieve the common heritage principle, and to encourage fair access to seabed resources by developing states, UNCLOS requires the ISA to reserve half of all identified mining areas for the ISA or for developing states (Annex III of UNCLOS, Article 8). These “reserved areas” should be of equal commercial value to non-reserved areas.

In 2021, the Republic of Nauru made a request to the ISA to adopt regulations to allow Nauru Ocean Resources Inc. to mine within a reserved area in the Clarion Clipperton Zone, an area in the international seabed between Mexico and Hawaii. Although Nauru Ocean Resources Inc. is a wholly-owned subsidiary of The Metals Company, a Canadian company, the subsidiary is considered to be a separate corporation based in Nauru, and thus has access to reserved areas. In 2023, the ISA agreed on July 2025 as a new target for finalizing the regulations. Nauru and Nauru Ocean Resources Inc. have indicated that they intend to submit an application for exploitation in June 2025.

Is the United States a Party to UNCLOS?

The United States is not a party to UNCLOS. The United States was part of the negotiations for UNCLOS but did not sign or ratify the convention. It objected to its deep seabed mining regime because, among other reasons, the United States was of the opinion that it would “actually deter future development of deep seabed mineral resources."

Several other industrialized countries also did not sign or ratify UNCLOS, and some states, including France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States began developing their own legal framework for international seabed mining separate from UNCLOS.

In response, the United Nations Secretary-General brought countries together to negotiate the 1994 Implementation Agreement to modify Part XI of UNCLOS. Even though the United States participated in these negotiations and signed the 1994 Implementation Agreement, it has still never signed UNCLOS, and as a result is not a party to either agreement.

What does the US Executive Order say about international seabed mining?

President Trump’s Executive Order calls on the US Secretary of Commerce to expedite the process for reviewing and issuing seabed mineral exploration licences and commercial recovery permits in areas beyond national jurisdiction under the Deep Seabed Hard Mineral Resources Act, to be accomplished within 60 days of the order. It also orders relevant authorities within the federal US government to provide reports on private sector interest in seabed mining, international benefit-sharing mechanisms and other tools to support seabed mining.

What is the Deep Seabed Hard Mineral Resources Act?

The Deep Seabed Hard Mineral Resources Act (DSHMRA) was enacted by the US government in 1980, prior to the adoption of UNCLOS and the establishment of the ISA. It was intended as an interim measure to allow US companies to engage in international seabed mining until an international legal framework (i.e., UNCLOS) was in place. But because the US has never ratified UNCLOS, DSHMRA remains in effect.

DSHMRA allows US companies to apply for licences for deep sea mining in international waters. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has only ever issued two exploration licences under the Act, both in 1984, and these licences have been extended to 2027. NOAA has not issued any exploitation licences under the Act. The Metals Company has stated that its subsidiary, The Metals Company USA, applied to NOAA for permits at the end of April 2025.

What will the consequences be if the United States actually issues these permits?

If the United States goes ahead with issuing permits to The Metals Company, it would open up the international seabed to a potentially dangerous activity, whose impacts are little understood. It would also undermine international ocean governance and could create a precedent for greater conflicts in the high seas, unleashing a race to the bottom. Other countries could also begin to take unilateral action on deep sea mining and other ocean activities like cable laying and fishing, leading to activities taking place without environmental oversight or sharing of financial benefits.

The promise of UNCLOS – that the international seabed should be the common heritage of all humankind, and that decisions on activities that have potentially far-reaching impacts should be made by international consensus – is in jeopardy.

What should Canada do?

Canada, as a party to UNCLOS and the ISA, needs to stand up for international law in this critical moment. Canada should join France and China in speaking out against the unilateral actions taken by the United States and The Metals Company, which circumvent UNCLOS and international marine law. The federal government should publicly re-assert Canada’s position supporting a precautionary approach to deep sea mining to protect the common heritage of humankind.

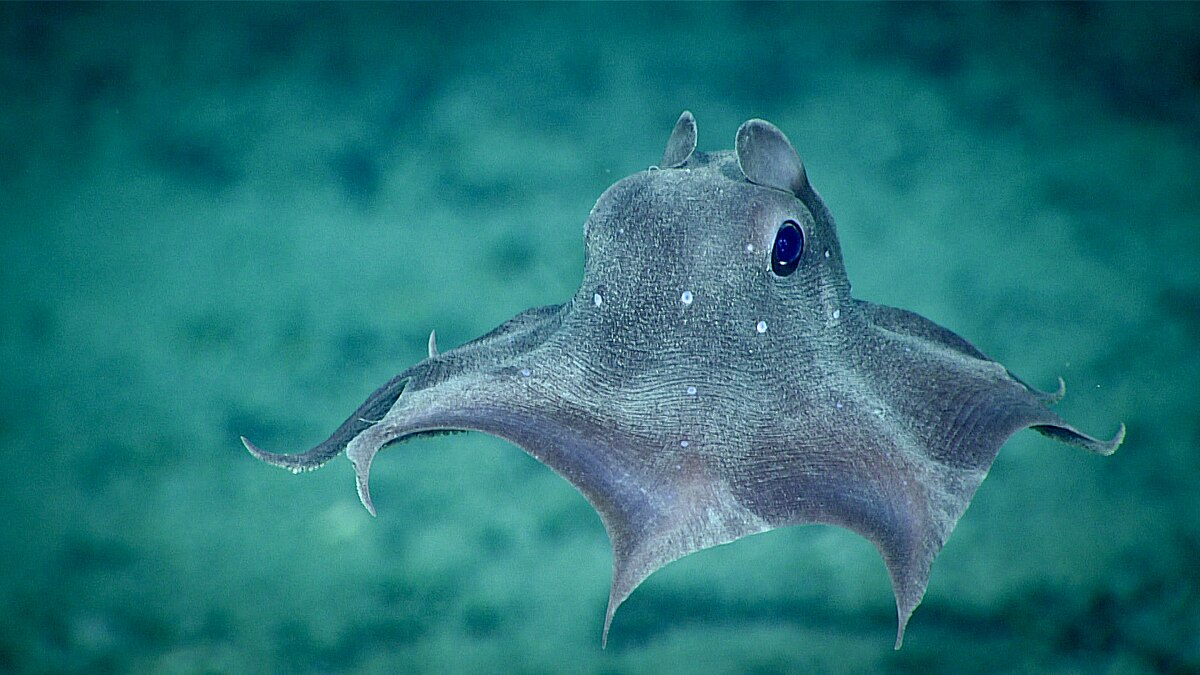

Top photo: Dumbo octopus / NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research via Wikimedia Commons