As BC rushes to rubber-stamp major projects aimed at boosting the economy, provincial leaders must not forget about the commitments they’ve made to ensure a healthy environment and uphold Indigenous rights.

The Infrastructure Projects Act (“IPA”), passed by the BC Legislature as Bill 15 earlier this year, allows for designated projects to be exempted from a wide range of existing legislative requirements. This includes many important requirements of BC’s environmental assessment process. While the Province plans to introduce a new “accelerated” environmental assessment process to replace the requirements removed by the legislation, they have not yet released any details about what that new process will look like.

Meanwhile, the Province has stalled in its commitment to prioritize and protect biodiversity and ecosystem health – protection that British Columbians agree should apply to projects designated under the IPA.

Weakening Environmental Assessment

There are many parts of the BC Environmental Assessment Act (“EAA”) that will not apply by default to projects designated under the IPA. Among these is the list of factors that must be considered in every assessment, as set out in section 25 of the EAA. This means that reviews of designated projects could avoid considering a range of important factors, such as:

- positive and negative direct and indirect effects of the project, including environmental, economic, social, cultural and health effects and adverse cumulative effects;

- risks of malfunctions or accidents;

- disproportionate effects on women or other distinct populations;

- effects on biophysical factors that support ecosystem function;

- effects on current and future generations;

- consistency with any land-use plan of the government or an Indigenous nation;

- greenhouse gas emissions, including the potential effects on the province being able to meet its targets under the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Targets Act; and

- the effects of the project on Indigenous nations and rights.

The IPA also allows projects to bypass opportunities for public comment, as well as processes for First Nations to indicate whether they consent to the project and for the government to seek consensus with First Nations.

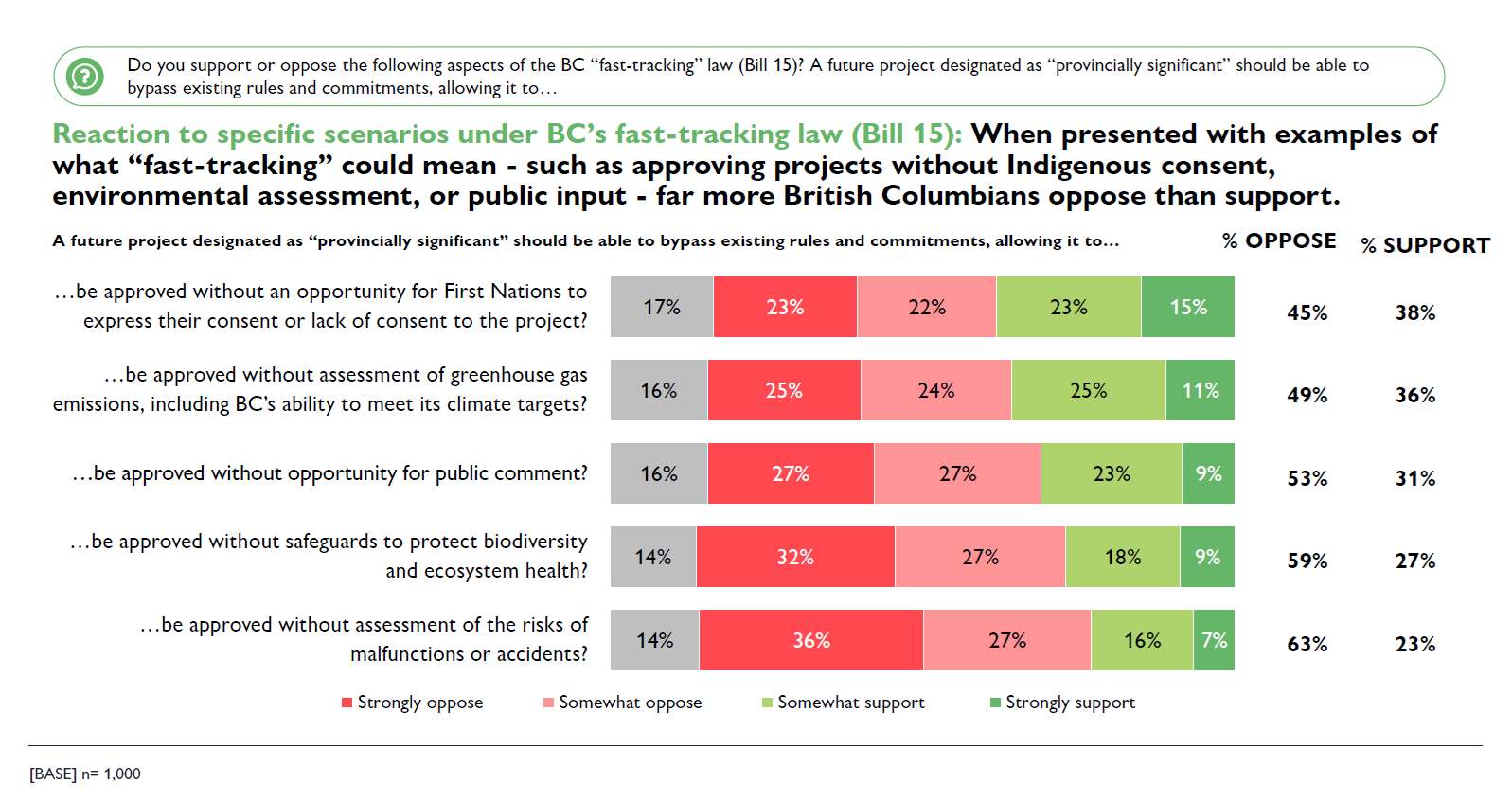

Removing these elements of the environmental assessment regime presents serious risks for adverse effects to go undetected or to be poorly understood by decision-makers – a fact that polling suggests British Columbians understand well. A polling question commissioned by West Coast on a recent omnibus survey by Abacus Data shows that British Columbians are not willing to sacrifice environmental safeguards or Indigenous rights to get projects approved more quickly.

While some people may generally support the idea of fast-tracking major projects, more British Columbians oppose than support bypassing rules regarding environmental considerations and Indigenous consent.

Four of the five specific exemptions queried in our poll refer to existing requirements of the EAA that may be bypassed under the IPA, and British Columbians are widely opposed to such exemptions. These results are consistent with other recent polling, including an Angus Reid poll on Bill C-5, the federal government’s fast-tracking legislation. That poll found that more Canadians opposed than supported “condensing or bypassing environmental reviews in certain cases.”

In addition to the changes mentioned above, the IPA also weakens the environmental assessment regime in other important ways. It allows for projects to bypass the entire early engagement process, including the option to terminate the process where it is clear that the project will have extraordinarily adverse effects; it removes the option for government to require an environmental assessment that would not otherwise be required if it is in the public interest to do so; and it removes the requirement for project proponents to report back on the effectiveness of measures taken to mitigate the environmental impacts of the project.

A recent report published by West Coast highlighted how cutting corners in environmental assessment and regulation can and has led to environmental disasters across Canada. Experience has also shown that excluding the public and attempting to shirk Indigenous consultation requirements can lead to conflict and legal challenges that do little to speed up projects.

BC’s environmental assessment regime reflects years of consultation, negotiation and careful development. The process cannot be easily condensed without sacrificing important substantive and procedural protections for the environment, human health, and Indigenous rights and title. West Coast takes the position that this cannot be done safely, and that the IPA should be amended to remove the environmental assessment exemptions altogether.

Undermining Commitments on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Health

In addition to existing rules under the EAA, we asked British Columbians whether “provincially significant” projects should be approved without safeguards to protect biodiversity and ecosystem health – and a substantial majority of respondents said they should not.

This question refers to the Province’s longstanding commitment, in response to the recommendations of the Old Growth Strategic Review, to enact a law to prioritize biodiversity and ecosystem health across all government decision-making.

The Province released a draft framework for biodiversity and ecosystem health in late 2023, and received nearly 8,000 mostly-positive responses by January 2024 (including from West Coast). Since that time, however, progress on the initiative has stalled, with the promised law nowhere to be seen.

Instead of taking action to prioritize and protect BC’s precious ecological resources and to ensure that new development takes place within these ecological guardrails, the Province is proposing to fast-track the approval of major projects that could undermine these commitments. Meanwhile, the Minister of Forests has been given a mandate to secure a land base that will enable the harvest of 45 million cubic metres of timber per year – a mandate without a clear economic basis that conflicts directly with efforts to protect biodiversity and ecosystem health.

West Coast is concerned that prioritizing and fast-tracking resource development in BC risks further eroding the biodiversity and ecosystem health values that the Province has pledged to protect, and polling suggests that a majority of British Columbians agree.

In submissions made jointly by West Coast and other allied groups in response to the Province’s engagement on IPA regulation development, we proposed adding a requirement for project proponents to demonstrate that their project will not jeopardize biodiversity and ecosystem health, BC’s climate commitments, or human health and safety. The Province can also act to prioritize biodiversity and ecosystem health through other existing processes, including by ensuring these factors are incorporated into the forest landscape planning process and by making use of best available scientific data on disturbance rates and risk in cumulative effects assessments, planning and permitting processes.

The Province must demonstrate that it takes its commitments seriously. This means finalizing its draft framework for biodiversity and ecosystem health and setting out a concrete plan to co-develop the new law alongside BC’s First Nations, as well as taking action now to preserve these key values until the new law is in place.

Top photo: Pete Nuji via Unsplash