H̓aíkḷa: To make things right – An opportunity for change

On October 13th, 2016, the Nathan E. Stewart, a tugboat owned by Kirby Corporation, ran aground and sank in Heiltsuk territory while transporting an articulated petroleum tank barge. The barge, which was thankfully empty, did not sink, however the tug itself spilled over 110,000 litres of diesel fuel, lubricants, and other pollutants into the sacred waters and Heiltsuk food harvesting site at Q̓vúqvái.

Since the spill, the Heiltsuk Nation has shown tremendous leadership in their pursuit of justice. From coordinating the initial spill response and clean-up, to conducting their own environmental and cultural assessment, the Heiltsuk continue their long history of exercising their Ǧviḷ̓ás (laws) and stewarding their territory.

On July 16th, 2019, WCEL travelled to Bella Bella to witness Kirby’s criminal sentencing hearing hosted by the Heiltsuk Nation. In this blog, we share reflections from this one-of-a-kind hearing that involved Heiltsuk and Canadian legal process operating side-by-side. We also provide a summary of the adjudication report prepared by the Heiltsuk Nation and of legal cases the Heiltsuk Nation is pursuing against Kirby in Canadian courts.

Dáduqvḷá qṇtxv Ǧviḷ̓ásax̌ - To look at our traditional laws

In addition to seeking redress in the Canadian courts, the Haíɫzaqv (Heiltsuk) have continued exercising their Ǧviḷ̓ás (laws) and asserting them when necessary in response to the Nathan E. Stewart incident. Despite ongoing colonialism and the imposition of the Canadian legal system over Haíɫzaqv peoples and territories, Haíɫzaqv laws have not disappeared and are increasingly being expressed by the Heiltsuk Nation for others to understand.

For example, the Haíɫzaqv are developing a written Constitution grounded in their Ǧviḷ̓ás (laws), and as part of WCEL’s RELAW (Revitalizing Indigenous Law for Land, Air, and Water) project, an Oceans Act – titled "Respecting and Taking Care of Our Ocean Relatives".

In response to the Nathan E. Stewart incident, the Heiltsuk Tribal Council established the Dáduqvḷá Committee “to assess and adjudicate the Spill in the context of Heiltsuk laws, known as Ǧviḷ̓ás, and prepare a written decision of its findings.” The first of its kind, the Dáduqvḷá qṇtxv Ǧviḷ̓ásax̌ - To look at our traditional laws adjudication report is a must-read.

The adjudication report begins by explaining the Heiltsuk understanding of law:

“Ǧviḷ̓ás means that we as Heiltsuk people derive our strength from our territory by following specific laws that govern all our relationships with the natural and supernatural world. It is the basis of Heiltsuk respect and reverence for the surrounding eco-system.”

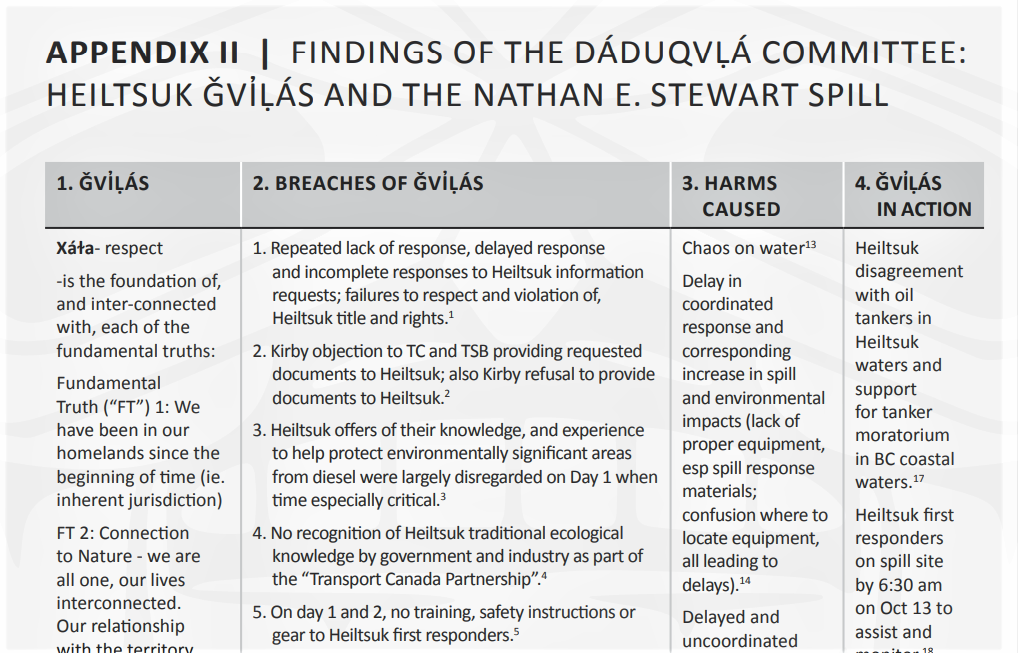

The Dáduqvḷá Committee explained the principles of Ǧviḷ̓ás, identified the misconduct leading to the spill to determine if Ǧviḷ̓ás were breached by the misconduct, assessed what harms or losses were caused by the breach, and identified the potential consequences to the wrong-doer.

An example of the approach taken by the Dáduqvḷá Committee is shown below.

Appendix II from adjudication report

In a section titled "H̓aíkḷa: To make things right - An opportunity for change", the report sets out a number of recommendations for Kirby, including;

- Attending traditional washing and healing ceremonies

- Apologizing to the Heiltsuk people for the spill

- Providing funding for Heiltsuk ecological and cultural restoration projects

The report notes: “their vessels are not welcome in Heiltsuk waters until they have acknowledged the harms done to the Heiltsuk as a result of their negligence and taken responsibility for their corporate misconduct and the misconduct of the NES captain and crew.”

Heiltsuk Ǧviḷ̓ás in action

This background provides a backdrop for the sentencing hearing we witnessed on July 16th, 2019. Unlike most environmental offences, which are prosecuted in Canadian courts in major cities far from where the harm took place, the sentencing of Kirby took place in the community hall in Bella Bella. As Chief Marilyn Slett stated, “We requested the hearing to be here because the spill was here and we are here.” The strength of Heiltsuk Ǧviḷ̓ás was palpable throughout.

The hearing involved a unique mix of Heiltsuk and Canadian legal process operating in parallel. The linear, hierarchical structure of a Canadian courtroom was replaced by a traditional sentencing circle. Heiltsuk Yím̓as (hereditary chiefs) attended in their regalia, Judge Brent Hoy in his robes, lawyers in suits, courtroom workers in black, the vice president of Kirby, elders, youth, leaders and witnesses all sat together in a circle surrounding cedar boughs and copper shields that were ceremonially drummed into the centre.

Yílístis Pauline Waterfall began by explaining the significance of the sentencing circle from a Heiltsuk perspective: “All parties who are impacted by an offence come together with their support people. Everyone can provide input and defenders will have an opportunity to explain the circumstances.” She explained that under Heiltsuk law, the consequences will always depend on the severity of the breach.

The adjudication report explains:

“…depending on the breach, the response could have ranged from death, to isolation or banishment, to being called before a council of Yím̓as or W̓iúmaqs (women of high rank) for accountability, to service to the community or to undertaking a ceremony within a feast or potlatch to acknowledge the harm that was done and to make amends.”

One by one, Heiltsuk representatives stood to present their victim impact statements and share the profound impacts of the spill now and for future generations. It was a difficult day for the community as they were forced to relive and recount the devastation in detail for the court.

“Our way of life and our relationship to this area will never be the same,” said Kelly Brown. “In times past and in some cases today, we have banished those who have threatened the safety of the Heiltsuk people.”

The Heiltsuk presenters unanimously called for all ships owned by Kirby to be banished from their territory until the company acknowledges the harm done to the community and responds to their recommendations in the adjudication report.

In Pursuit of Justice: Canadian legal cases against Kirby

The Crown charged Kirby with nine counts related to the Nathan E. Stewart incident. Kirby pled guilty to three of these counts, including:

- Depositing a substance harmful to migratory birds under s.5(1) of the Migratory Birds Convention Act

- Depositing a harmful substance in water frequented by fish under s. 36(3) of the Fisheries Act

- Proceeding in a compulsory pilotage area not under the conduct of a licensed pilot or the holder of a pilotage certificate under s. 47 of the Pilotage Act

Kirby and the Crown prepared a joint submission on penalty, which was presented to Judge Hoy during the sentencing hearing. Judge Hoy agreed with the proposed sentence and imposed close to $3 million in fines for these three offences.

In his written judgment, he noted:

“The Heiltsuk Nation pointed out in the course of the Talking Circle that no amount of monetary fine could justify the damage that had occurred to their traditional lands. Their expressions of frustration and anger are understandable. Their heritage and traditional lands and waters were contaminated by the spill. These legitimate sentiments could never be properly addressed within the context of environmental prosecutions.”

In response to the Heiltsuk’s request to have Kirby banished from their waters, Judge Hoy simply stated that he does not have the jurisdiction to make such an order.

Though these fine amounts are among the highest ever awarded for these environmental offences, they do little to resolve the concerns of the Heiltsuk Nation. In an open letter from Chief Marilyn Slett to the CEO of Kirby entitled “Does Kirby Care?” Chief Slett notes these fines are “a drop in the bucket for a multibillion dollar company and one of the world’s largest tank barge operators.”

Chief Slett explains in the open letter:

“We both know this sentence does not represent true justice. True justice would mean paying for an environmental impact assessment, admitting civil liability, and working openly and honestly to address compensation and remediation for the harm caused by the spill. You should work with us to help reform antiquated marine pollution compensation laws, rather than hiding behind them.”

In their pursuit of justice, the Heiltsuk Nation launched a civil case against Kirby to cover the cost of losses to commercial clam harvest, communal harvest, cultural losses and the cost of an environmental impact assessment, among other remedies. The Heiltsuk Nation is also challenging Canadian law that does not allow compensation for seafood harvesting and cultural losses.

Conclusion

After the Canadian court proceedings were said and done, the Heiltsuk Nation invited everyone – judges, lawyers, offenders, victims, community members, and witnesses – to a feast followed by a blanketing ceremony for Judge Hoy to acknowledge his openness to Heiltsuk Ǧviḷ̓ás. From the perspective of a Canadian-trained lawyer working to uphold Indigenous laws, it was heartening to see this openness to Indigenous law and protocol in a Canadian court proceeding and to be able to imagine creating “space for Ǧviḷ̓ás to be afforded full recognition as a legal order” (adjudication report).

One can picture a future where the decision-makers in this case – hereditary chiefs and/or Canadian judges – spend time deliberating the Heiltsuk Nation’s substantive position that Kirby Corporation be banished from their territory until Kirby can prove it no longer poses a threat to Heiltsuk territory.

As it stands, significant challenges remain to implementing and enforcing Heiltsuk Ǧviḷ̓ás through Canadian courts, and indeed this may not be the preferred venue. Meanwhile, the Heiltsuk Nation are still in pursuit of true justice, still working to enforce their Ǧviḷ̓ás and restore their territory for generations to come.

Learn more about this case and how to support it here.

Photo credit: Georgia Lloyd-Smith